THE CLOD

Tom Ianelli

There is a certain tech company building that is, unsurprisingly, full of secrets. It’s stuffed to the brim with them. Secrets fill the air like humidity and drip thickly down the walls, puddling invisibly on the floor.

This building is the Glandis western regional center. Erected next to a lake in the 70s, the building is very beautiful from the outside. It’s sleek and white, with big mirrored windows covering entire walls. The trees on campus are yellow, and the grass is a fried yellow-green. Nice colors against the white building and the gray sky of a fall morning.

Inside, however, the light is flat and the day has settled into its usual routine. The employees study the markets and data and boring shit like that. Work so dull that, when they mention it at a party, people’s eyes instantly glaze over. But they don’t mind. The pay is, of course, quite competitive.

In an office on the second floor, Bennett Parker, the director of operations, is sitting behind his desk. Bennett is a sturdy man with massive, uncalloused hands, and today he has those big, soft hands plopped on his desk in front of him, inert and open. He feels bad that his big hands are so soft. He looks out the window at the lake and the forest beyond. When Bennett was young, he had a strong notion that one day he would cut up his ID cards and go live in the woods. That had been his plan. To abandon society and live by simpler, primordial laws. He loved that word. Primordial. It made him feel tapped into an essential form of freedom that others were too soft to engage with.

But then at some point in college this notion abandoned him. He doesn’t remember when or how it happened. Just that at a certain point he no longer pondered primordial things. He no longer dreamed about being free.

Bennett looks at the lake and thinks he is disappointing his younger self by being who he is. By managing people. By being a pussy, like his brother so often claimed he was when they were kids. He thinks about that every day. About whether he’s a pussy or not. Sometimes only for a moment. Sometimes all day long. Today, as it often does, the thought makes him sad, so he stops thinking about it and gets back to work.

Louise knocks on the door frame and walks into Bennett’s office. She asks him a question and watches his mouth as he answers. Louise hates Bennett's stupid face. His balding hair. The mole on his stubby nose. Bennett is ugly and obtuse and he has that white stuff on the corner of his mouth but he still has all the confidence in the world. Louise thinks it should get beaten out of him.

All her life Louise has hated people. She thinks she is better than others for no reason at all. Hatred burns inside her like a furnace and everyone she sees gets thrown in. The hatred is so strong that she is afraid of it. She protects it from coming out at all costs, which has made her a meek and frightened person. Looking at Bennett, she realizes he is done talking and she didn’t hear a thing he said.

“Anything else Louise?” he asks with a smile.

She wants to smack the smile off his face. “No, thank you so much, Mr. Parker,” she says. “Of course, Louise.”

Keep my name out of your fucking mouth, she thinks. She watched the Will Smith slap video at her desk earlier that day. It’s her favorite video on the web.

“Thanks so much again,” she says, and leaves.

Devin is in the kitchen when Louise walks in. Louise had called him “Dev” once and Devin wishes she would call him “Dev,” all the time.

“Hey Devin,” she says.

Fuck, he thinks.

“Hey Louise,” he responds.

Devin hates his name. Devin. He spends a lot of time wishing it was something else. He wants to be named Primo or Federico. He blames his parents. Their names are Mina and Wyndham and they named him Devin. He’ll never forgive them for that.

Devin makes coffee and Louise microwaves soup. Devin thinks briefly about what Louise might look like naked and, coincidentally, Louise thinks the same thing about Devin. There is nothing sexual in these thoughts. They are produced by boredom.

Michelle sneezes in the next room and both Devin and Louise groan. Michelle sneezes 25 times a day and her constant sniffling is impossible to ignore. Blow your fucking nose Michelle, they think.

She sniffles.

Their lives are tortured and burdensome and the sniffles are like a hammer banging down the nails of these facts.

Another wet sniffle.

The mood in the kitchen is dense and narrow. Louise and Devin both think they can’t handle it anymore. Perhaps life isn’t worth living.

But then after a few minutes, they both look up. Something is different. They pause. They wait for a sniffle but, somehow, it doesn’t come. Two minutes pass, and then two more. The air begins to clear.

A few more minutes pass, and still no sniffle.

Devin takes a sip of coffee and it’s a small miracle how good that coffee tastes. He looks in the cup and takes another sip. He nearly moans. Free from the sound of the sniffles, the second sip seems even better than the first.

Blessings are everywhere, he thinks.

Behind Devin, Louise pulls her soup out of the microwave. In the newfound silence she takes a spoonful and it burns the roof of her mouth. But that’s not so bad, she thinks, suddenly optimistic. Her mouth will heal. What a thing, the body’s ability to heal itself. I think I’ll go to church this weekend, she thinks. And the thought makes her happy.

In the silent kitchen Louise and Devin turn towards each other. There is a magnetism pulling them together. A golden force of love. They have the urge to hug one another. They are going to do it. They lean in the slightest amount, both of their mouths curling, almost imperceptibly.

But then Michelle gasps and sneezes three times in quick succession and, with an iron force, the darkness descends on the office kitchen once more. They see that their hope was pointless, a mirage, and just like before, such a life as theirs is hardly worth living.

Michelle herself is the only content one in the office. There is no reason for this. But she is unbothered. A genuine optimist.

When she gets a bad haircut it doesn’t destabilize her.

She doesn’t delay picking a movie, she just makes her choice and lives with it.

She has been cheated on and both of her parents died young but she was able to experience these things with an appreciation for life’s sad, mysterious depths.

Now in her early fifties, her dog Michael is genuinely all she needs.

She sneezes again. She’s allergic to something in the office but it doesn’t bother her much. It just makes her, as she puts it, ‘a little sniffly.’

She hears a groan from the other room but has no clue it might have to do with her.

She looks through the far window that faces the parking lot and sees that Terrence is outside sitting in his car. It looks like he is staring right at her. She waves but he does not react. He just goes on staring. She wonders what he is doing.

Terrence is not doing anything. It seems to Michelle like he is looking at her, but that’s because the windows are mirrored and she doesn’t realize that. Really he isn’t looking at anything. His eyes are just resting. He is looking at nothing and doing nothing and nothing is happening. There is no good reason for Terrence to do nothing like this. On a normal day he opens the door and goes right into the building. But today he didn’t do that. After he parked, he stayed in the car for no reason and now, the more he stays there, the more nothing happens.

Terrence isn’t depressed. His wife didn’t leave him. He doesn’t even have a wife. He’s gay, in fact. But that doesn’t have to do with it either.

Terrence thinks how he could conjure up some reason for his pause. He could attach an existential dread to the stillness of the situation. But he thinks the words existential and dread are meaningless. So he avoids them and just sits there.

He just sits and notices a certain suctioned silence in the car. But almost immediately, he is exhausted too by how unoriginal it is to notice such a thing. Terrence is sure that whenever white collar workers sit in their cars, afraid to go into their homes or offices, they also probably notice how the seal of the doors makes the inside of the car have that hollow soundlessness. They probably attach some emotional significance to it. Calling it a metaphor for the hollowness of their beings, their lives.

He frowns. Beings and lives. How fucking stupid. Who cares about life and being. It’s so dry. So played out. But, he thinks that it’s also dumb to be so jaded. For everything to seem so perpetually unoriginal.

He should just be able to simply be. To simply breathe. So he does just that. He breathes deep.

But god, as his lungs fill up with air, he can’t get out of his mind how played out breathing is. It’s what everyone uses to feel better. And to what end? They breathe and breathe but the moment they stop thinking of their breath, the problems are still there waiting for them.

And I don’t even have a fucking problem in the first place! Terrence thinks. I’m just sitting here. Can’t I just sit here and do nothing without there being a problem?

He slaps the steering wheel and as he does, something moves outside. He looks around. He looks at the sleek building. The scene is still and quiet. The building is the same as it has ever been. But when he looks up he sees that on the third floor, one of the mirrored windows is moving. Warping ever so slightly. Almost as if something might be pushing on it from the inside.

Inside the window, the Clod is staring at Terrence, pressing up against the glass. The Clod lives in a large room with cushioned vinyl floors and drains at the walls’ far ends so the discharge can be harvested. Behind him hover a handler and harvester in slim marshmallow-yellow hazmat suits. Both are named Johnson.

“It’s really stimulated,” says Harvester Johnson.

“Twenty bucks on gassy,” says Handler Johnson.

A wet fart sound emanates from the Clod.

“Told you,” says the Handler.

“It’s always gassy.”

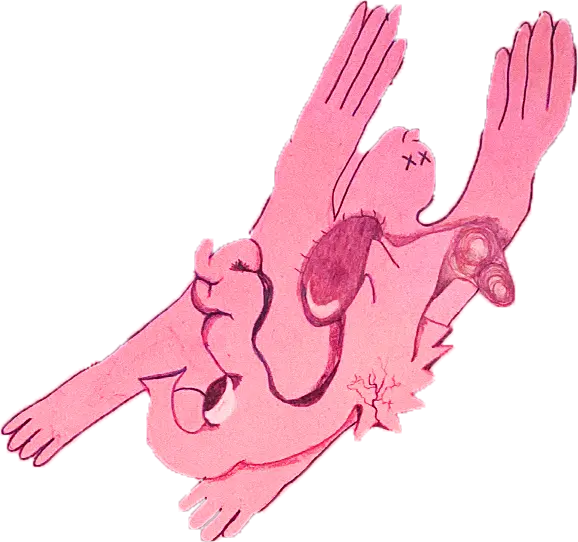

The Clod is large and hairless. It resembles a manatee, but walks and has arms like small paddles. Its skin is usually a shriveled pale blue, but when stimulated, it swells and turns translucent pink, excreting a creamy substance called Jizz that plops off in heavy clumps.

That’s what the harvesters are here for. To keep it producing. Watching Terrence through the glass, the Clod groans and drags white streaks of jizz across the window.

This, incidentally, is where the word jizz comes from. A century ago, a loose-tongued technician from Glandis Jizz Division let it slip while drinking in Key West. The word shot sporadically across the country, and though the company executed the man for the leak, they allowed the slang to live on.

Some say the Clod was found in a mine, others in a lab, but the truth has been swallowed by corporate mergers. The genesis is unimportant. All that matters is the jizz. Refined and sold under the trade name X9 through a subsidiary called Xyntra Materials, trace amounts of Jizz end up in everything: face cream, gasoline, silicon chips, oat milk. Jizz sustains whole markets without a single public mention.

Harvester Johnson mops the Jizz toward the drains, careful to keep a wide berth. The Clod’s jizzing is its version of salivation. It’s a reflex that, in excess, turns lethal. Researchers long ago discovered it reacts most strongly to a certain kind of person: the obedient worker who trades real desire for the safety of a paycheck. People who once wanted to write, paint, travel, or simply be free, but learned to channel all that energy into performance reviews and polite ambition. Those who convince themselves they’re happy because the world tells them the money should make them so and in doing so, they emit a metabolic byproduct, a kind of emotional exhaust, that the Clod feeds on. The stronger their repression, the richer the feed.

Thus, the Clod jizzed watching Bennett stare at his own hands. It jizzed watching Louise swallow her hatred for Bennett. It jizzed at Devin’s shame over his name, and it jizzed like crazy at the effete Terrence sitting in his car.

Under the banner of the tech boom, Glandis built the Western Regional Center and filled it with the right kind of worker: loyal, efficient, emotionally starved. They keep the Clod jizzing without ever knowing it’s there. Over time, the model proved so profitable that Glandis assumed Google, Meta, and now ChatGPT, all of them must have their own clod. How else could the market move in such perfect sync? No one says it outright, but the complicity is obvious. The offices, the slogans, thousands of employees working with total conviction, unaware their only purpose is to make a giant secret penis monster jizz.

Due to the perceptivity of the Clod the company maintains a strict recruitment process for harvesters and handlers: men devoid of pensiveness, certain of themselves in the most militaristic way. Cold, simple, self-contained men in their forties. They work five years, and then never have work again.

Still, flaws occur. That morning, as he entered the building, Harvester Johnson locked eyes with a boy who looked exactly like Ralph Macchio. His training did not account for this. He was as rigid and controlled as training demanded, yet at the sight of Ralph, or this uncanny facsimile, a knot he had forgotten existed loosened in his loins. He always had a soft spot for Ralph Macchio.

Mopping the jizz, Harvester Johnson tries to remember his training, but the beautiful, hurt face of Ralph from The Outsiders stays pasted behind his eyelids. He flushes. He’s always wanted a friend like that. A friend who saw him.

The Clod’s head cocks slightly, as if listening and lets out a wet, bubbling purr. It’s paddle-hands peel from the window and it turns slowly toward the two men. It’s face sloughs off in pink clumps and Johnson prays it orients toward the screens, anywhere but in his direction. But Ralph’s face flashes again, tender and forgiving. No one had ever looked at him that way. Johnson wonders if he wasted his life, mopping up jizz, forbidding love to enter his heart.

The Clod burps, then purrs, and looks right at him. Johnson had never met the Clod’s eyes before. Bloodshot with violent hunger, they’re nearly human, as if someone is stuck in there, straining to get out. The Clod moves toward him, and a thought lands cold in his gut: this had been the plan all along. The Jizz Division hadn’t missed Ralph Macchio’s place in his heart. They’d chosen him for it. A more substantial meal for the Clod.

He looks to Handler Johnson. “You knew,” he says, but Handler Johnson makes no sign.

Harvester Johnson closes his eyes and thinks of Ralph looking up at him from his death bed, neck covered in burns. His eyes are soft, gleaming, as if Johnson were his best and only friend. He touches Johnson’s cheek. “Stay gold Pony boy,” he says.

Once the Clod has fully consumed Harvester Johnson, his replacement harvester enters the room. There is a river of jizz in the room, and while the handler gets the Clod’s attention back to the screens, the new Johnson quickly squeegees the liquid gold toward the drain.

Once clean, they shut off the screens, shutter the windows of the room and after a minute, the Clod’s skin shrinks back to its natural wrinkled, pale blue color. It stands in the center of the room, slightly bent.

When unstimulated, this is all the Clod does. It sits in the center of the dark room, unmoving, its manatee head tilted downwards. It almost looks sad. Or ashamed perhaps. Researchers have determined that the Clod is unthinking. That there is no deeper misery in the unstimulated Clod. They say that it is like a light turned off. Yet still, the Clod seems sad. Perhaps there is a frequency of something happening that the researchers are unable to comprehend. Or perhaps not. In either case the jizzing beast sits there for hours, inert and alone in a dark room while the world spins around it.

Outside, Terrence finally gets out of his car. His boyfriend sent him a text telling him not to eat a big lunch because he’s going to make him a special dinner. Terrence smiles as he walks inside.

Michelle sniffles and says hi. Blow your goddamn nose, Michelle, he thinks. “Hi, Michelle,” he says.

What a nice guy, Michelle thinks.

At her desk, Louise briefly imagines masturbating that night. She’s looking forward to it.Devin is in the kitchen watching NBA highlights on his phone. It’s the playoffs, and he fucking hates the Celtics. It almost feels good to hate something that much.

A new email from Bennett Parker pings at the top of the screen. “Dumbass bitch,” he mutters, swiping it away.

In his office, having just emailed Devin, Bennet opens a new tab.

On his lunch break he had seen a guy with a youngish face step on to a thing, a strange platform with a single wheel in the center.

“What in the world is that?” Bennet asked.

”It’s a one-wheel bitch,” the kid had said.

Bennett stood there, arms crossed and watched as the kid stepped on to the thing, bent his knees, and flew off down the road. Bennett gasped. He had never seen something like that. The boy looked so free.

He surfed the web and did some research. He blushed. He wasn’t the extreme sports type. But he did have good balance. He found a beautiful GT S series electric blue accents. Redditors said it was the only one to get. Great for learning. He put in his address and card info. But on the final checkout page he paused. He looked out the window and wondered if he was a pussy or not. He sighed. He sat back in his chair. He sat like that for five minutes.

Ralph Macchio! he thought suddenly. That was who the kid on the one wheel looked like. He looked just like Ralph Macchio in the Karate Kid.

Bennett thought of the kid flying away. So stable. So cool. He took a deep breath and as soon as his eyes hit the screen he clicked confirm purchase. The screen loaded, and there it was, his purchase confirmation.

He really did it. He was shocked. He clapped, jumped up and danced around the room. He kept looking at the image of the OneWheel. It was so beautiful.

He picked up the phone. He dialed, brought the receiver up to his ear and waited.

”What’s up pussy,” the voice on the other end said.

“Hey Mark,” Bennett said, deepening his voice, trying to hide his excitement. “You’ll never guess what I just bought.”

TOM IANELLI is a fiction writer and street bookseller in Williamsburg Brooklyn. He asks the questions for the Lit Chat instagram series at @peterbooksnyc. He has written for The Panacea Review, Quartersnacks, Bruiser Mag and Farewell Transmission.

← back to features