SKIPPING CLASS AS PRAXIS

Petra Cortright

I dropped out of two art schools. I was a horrible student at both, always skipping class to work on art projects at home on my computer. That ended up being my biggest saving grace as a working artist.

TESS POLLOK: You’re an artist who works across digital mediums, painting, and video. One of our readers was just telling me about how much he loves your ASCII drawings. Do you have any upcoming projects or shows people should know about?

PETRA CORTRIGHT: Yeah, there’s two. I have an installation at Art Basel this year and a week later I have my debut museum show opening in Switzerland at Zeughaus Teufen. That’s been in the works for almost three years now. It originally was meant to open on my due date. [Laughs] I was like, “That’s not going to happen.” But it’s finally happening this year, and I’m showing new wood paintings from my practice over the past few years.

POLLOK: You grew up here, in Santa Barbara. How did that influence your work?

CORTRIGHT: My parents are both artists. My dad, who passed away when I was four, was the head of the art department at UCSB. I was heavily influenced by them, initially. I paint so many landscapes when I’m in Santa Barbara–the mountains, the ocean. I’ll never shake it. I think my landscapes, even when they’re of other places, always have a very Californian quality to them because of Santa Barbara.

POLLOK: When did you decide to incorporate the internet into your practice?

CORTRIGHT: I’m of the age where I was able to have a very analog childhood. I didn’t get my first computer until I was about 10 or 11. I was really into SimCity and other building games at first. I have an older half-brother who’s a graphic designer and he got me into Photoshop at an early age. Randomly, there was a digital art program at my high school in 2002, which I took. When I was growing up, I would say 25% of people or less were on the internet–now, obviously, that’s much closer to 100%. But I like to think I’ve been living the way people live now, I just got a head start.

POLLOK: What have you been working on recently?

CORTRIGHT: I’m actually working with a gallerist in LA to put together a third show, hopefully later sometime this year. But we lost a 200-year-old oak tree in the Altadena fires and this particular gallerist really has a thing for oak trees. So I’ve been taking pictures of the coastal oaks here in Santa Barbara over the past few months and doing paintings of them, as well. They were really pretty earlier in March, very foggy and green. I also have some seascapes that I’ve been working on. Again, it’s all heavily influenced by Santa Barbara, since we had to move back here after the fires. It’s kind of weird being back in my childhood town but it’s definitely influencing my work. But I don’t like to talk about work too much while it’s in progress, because sometimes the paintings don’t come out how I envisioned them.

POLLOK: We had a craft talk on that topic recently and we talked about how artists like talking about their work while it’s in progress and some don’t. There’s mixed advice on that topic. My friend Peter once told me that talking about the work before it’s finished is like letting air out of a balloon.

CORTRIGHT: That’s a good way of putting it. It’s helpful for some people but I never find that it makes anything better for me. If anything, it takes away from the work to talk about it beforehand. At some point you have to just do it, you know? But I don’t even know what that means anymore.

Ever since I became a mom, there’s so many ways that I have to work now that are not ideal, so I know it’s not going to kill the show just to speak on it. I used to make work in a much more idealistic way, especially when I was younger, just always trying things out–that’s just not possible for me now. Having a kid while being at the studio is so, so challenging. Especially with two, technically three shows coming up, it’s like working with my hands tied behind my back. It’s extremely chaotic. But I think that comes with the territory of motherhood, you just push through things you think you never could have done before and you do them because you have to.

POLLOK: Has being a mother changed or influenced your practice in any other ways?

CORTRIGHT: It’s mostly about not having long periods of time to work. It used to be that if I was feeling really good one day I’d paint for 12 hours or more. That’s not something that’s possible when you become a mom, your time becomes much shadier and more fragmented.

POLLOK: We’re actually in Santa Barbara right now because you and your family were impacted by the fires, right? I heard that your house didn’t burn down but the damage from the smoke and debris was such that it became unsafe for your kids.

CORTRIGHT: That’s right. My husband was also affected because he stayed back during the fires to spray our house with water and now he has asthma. It’s been crazy. Clean-up after a fire like that is the most all-encompassing project, it’s a full time situation for us. For anyone who has kids, you have to be 50 times as careful. I don’t trust a lot of what the officials say about the situation because there have been so many massive infrastructure failures that contributed to this fire in the first place. You really have to take things into your own hands and do your own testing. Our house is older so the windows weren’t sealed as well against chemicals and there’s so much that comes into your home when there’s a wildfire of that scale. We had an independent company test our furniture and all of our things and there were insane levels of arsenic, lithium, things like that. Really bad stuff, obviously we don’t want our kids around that.

Summer by Petra Cortright. Courtesy the artist

POLLOK: Something I read on the news that really put the fires in perspective for me is that it’s LAFD policy to send two to three fire trucks and 15 firefighters for a single house fire. So, when you multiply that by the scale of the Altadena and Palisades fires, you start to get a sense of the scope of the infrastructure failure. We don’t have a million fire trucks.

CORTRIGHT: It’s just catastrophic. Every single day, there’s something that has to wait until the next day. I’ve just learned to accept that about the situation. It’s taken us 5 months to find a mediator that we want to use for the insurance. A lot of people still don’t have good answers for how to clean things or if things even can be cleaned–I think we’ll end up having to throw most of our possessions away. The mediators are the ones who have to call the insurance and make the final decision about how much is a total loss, so it’s important to find a good one. There’s just no protocol for something on the scale of these fires and my heart breaks for people whose houses actually did burn down. When I think about what we’re dealing with, knowing that we’re one of the lucky ones–I mean, I know people on our street whose insurance had expired before the fires and they’re living out of camper vans outside the ruins of their home.

I know people who are paying for cleaning services right now and they cost anywhere from $20,000 to $80,000 to do an entire house. And if you don’t do it right the first time, it’s not something you can do again, because insurance won’t pay for it a second time. Everything feels like a gotcha moment with the insurance companies right now. They’re always looking for a reason not to pay for stuff.

POLLOK: I’m sorry you’re going through that. There’s an Altadena Eaton Fire Relief Fund on GoFundMe that was established by the Altadena Town Council, if anyone wants to donate. Are you feeling better now that you’ve been able to relocate to Santa Barbara?

CORTRIGHT: Definitely. I’ve lived in lots of places across the world but I’m always happiest in California and the American West. I love being able to see so much of the landscape and see so far around you. I love vast landscapes, like Montana, or being able to see the ocean. One thing that’s nice about being in Santa Barbara again is being able to be by the ocean. It’s hard for me to explain how important the ocean is to me–it’s funny because my husband is from the Midwest and he just doesn’t get it. It’s calming. I grew up here, so it makes me happy to be near it.

POLLOK: It sounds like landscapes are an inspiration to you, like they are for many artists. What else inspires you?

CORTRIGHT: Oh my god, so many things. I have to show you the Recently Saved folder on my computer, there’s so many paintings and images of things that inspire me. If I see a painting that I like, I’ll use it in a collage. That’s one of the advantages of being a digital artist. I enjoy consuming the things I love and using them as underpaintings, or as composition guides for the work. You can do that technique with traditional painting, as well, but it’s faster with digital.

POLLOK: Who were some of the people who inspired you to become an artist? How did you know that art was something you wanted to pursue as a lifelong goal and career?

CORTRIGHT: I literally just failed at everything else. [Laughs] I trained to be a soccer player, initially, but I turned down all the full ride scholarships I got in high school to go to art school instead. My mom was so disappointed in me for doing that, I remember, as an artist herself she was just in the corner face-palming that I would do something so incredibly irresponsible. I sometimes think about whether I should have pursued the soccer route but I don’t have the personality for it. You have to have such a singular focus on the sport, which I lack, and there’s a mental toughness to being an athlete–I’m too nice. Being nice only gets you so far in the world of sports, at some point you have to be ruthless.

POLLOK: Where did you end up going to art school?

CORTRIGHT: I dropped out of two art schools. I went to California College of the Arts for a semester, right after high school, and then I did the same thing at Parsons later on. CCA is in the Bay Area and I thought I would like it because it’s a big city, but I ended up hating it and all the people there. It just wasn’t exciting to me. I really wanted to pursue graphic design but there was no program to use a computer and be creative there at that time. I was a horrible student at both schools, always skipping class to be working on some other project on my computer. That turned out to be my biggest saving grace as a working artist.

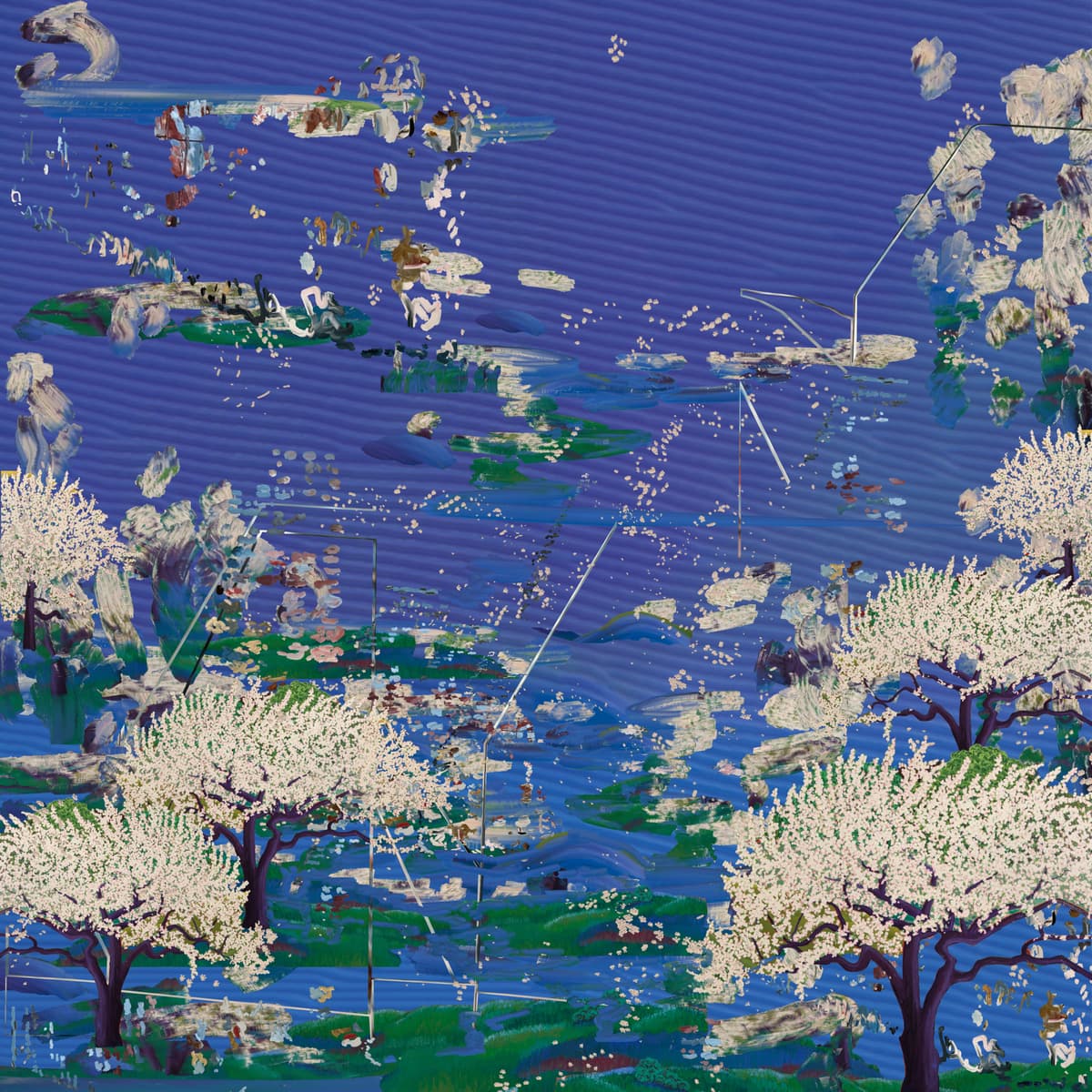

Spring by Petra Cortright. Courtesy the artist

POLLOK: Do you want to talk more about your work at the MoMA? Our readers love it, obviously, it’s probably your most famous work. I’m curious about how it ended up in their collection and how you’re feeling about it now.

CORTRIGHT: It’s a webcam video I made. It’s honestly a pretty boring video. I come from a group of artists who are obsessed with presets and defaults in terms of digital art, notably including Cory Arcangel, Michael Bell-Smith, people like that. We were interested in the vlogging medium and early YouTube videos that were coming out. I wanted to make art in the most interesting way I could with the least amount of steps. I was given an assignment to make something at Parsons so I went to the Union Square Staples–which is still there, by the way–and bought the shittiest webcam I could afford for $19.99. I didn’t want to check out equipment from the school and I didn’t want to work with any of my classmates because I didn’t like them, so I used the webcam to make video art by myself in my room. I made all of it with the effects that came on the camera. I think it feels a bit snarky, looking back at it now, the way I used only default presets. I love working by myself. Artists are just too serious. Sometimes it’s a little much for me.

PETRA CORTRIGHT is an American film and digital artist.

TESS POLLOK is a writer and the editor of Animal Blood.

← back to features