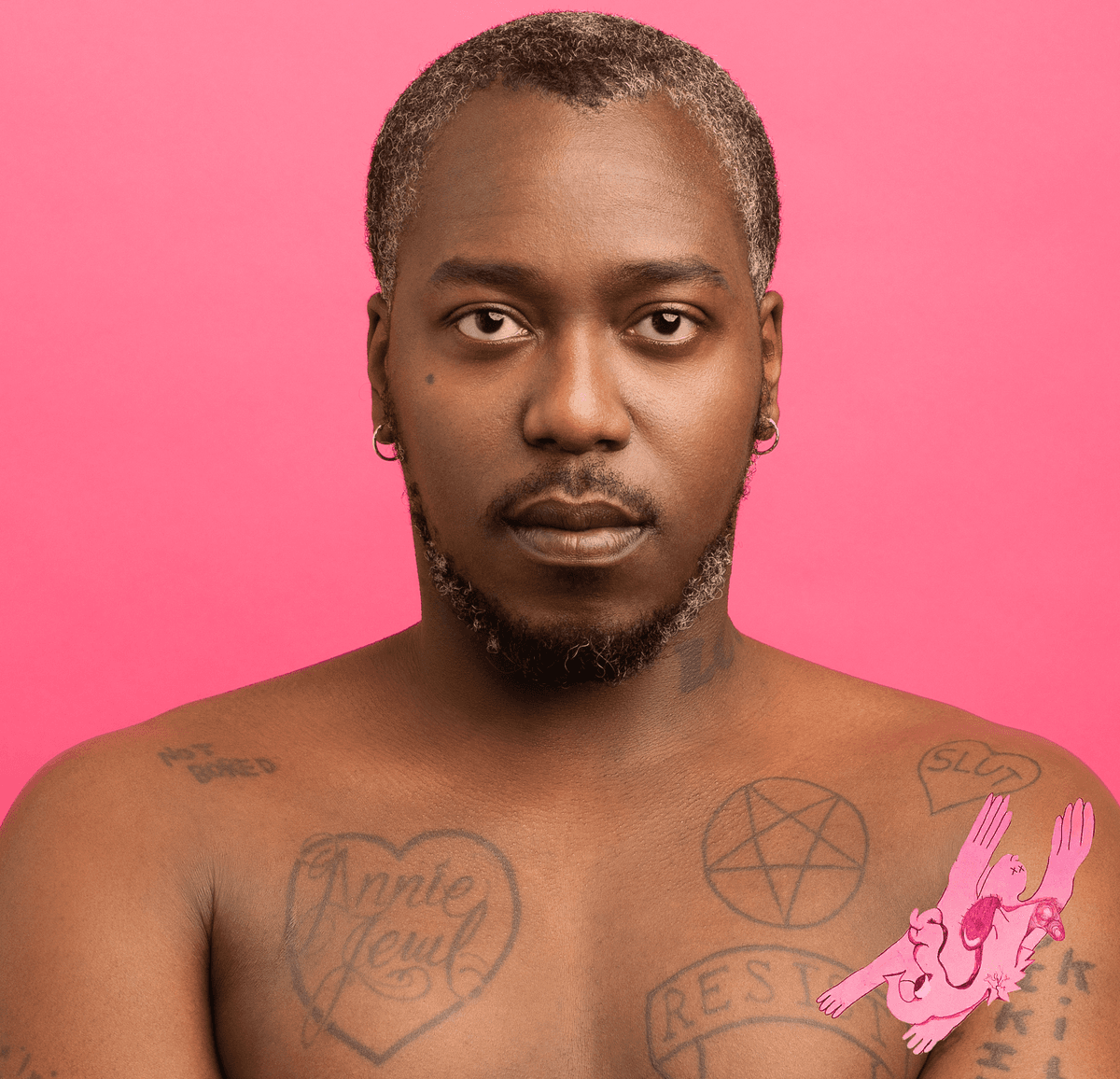

READING IS DANGEROUS

Brontez Purnell

It was a long decision for me, when I was partying really hard and drinking really hard, to make a serious decision not to kill myself directly or slowly. Since I’ve already made the decision to live, I have to find a way to coexist with my trauma. I’ve learned how to do no harm to others and to minimize the harm to myself. It’s a lesson you spend your entire life learning.

TESS POLLOK: You’re a writer–you’ve actually written a hefty amount of books, including 100 Boyfriends and, most recently, Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt. 100 Boyfriends won the 2022 Lambda Literary Award for Gay Fiction. When did you know that you wanted to be a writer?

BRONTEZ PURNELL: I’ve been writing since I was 14 years old. My mom’s thing is literature so I got it from her. My mom had me reading Black Boy by Richard Wright in the sixth grade. Literature was sort of always there for me. It was like witchcraft for me, coming to understand the story–feeling it all unfold in my mind, understanding that one thing doesn’t just mean one thing and that you have to piece everything together. I feel like reading is how I realized that people have thoughts. It’s powerful to be a reader, and also dangerous.

POLLOK: What did you connect with reading in your early life?

PURNELL: I remember the first book I ever read, it was a chapter reader from the late ‘80s. It was a fable about a farmer who went to the wise man complaining he had too many children. The wise man told him to add a chicken to his house and then a donkey. And then a cow. Then he told the farmer to take away the chicken, the cow, and the donkey, and the farmer was finally at peace. I read it out loud to my mom and talked with her about additives and about space–it was the first time I really understood subtext. That story has two meanings. It was a powerful experience to learn from that.

POLLOK: I love that your mom is an inspiration to you. What did she do?

PURNELL: She was a secretary, but she wanted to be a writer. Sometimes I feel like I’m living a lot of my dreams for her. My friend brought up this John Quincy Adams quote to me the other day–”I am a warrior so that my son may be a merchant so that his son may be a poet.”

POLLOK: I’m really interested in your newest book, which is a memoir. What was the experience of writing Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt like for you?

PURNELL: That was a crazy summer. I was writing three books at once, literally. I started a poetry collection and a sci-fi book–the sci-fi book is still incomplete. Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt was the only thing I started that summer that I actually finished. I call it a memoir in verse almost as a joke, because I feel like critics always act like People of Color, women, all marginalized people–they always say that we’re all writing memoir.

POLLOK: You’re working on other books? What about your sci-fi project?

PURNELL: It’s about a family of psychics at war with each other. I wanted to write something more removed from our urban tumult. I needed something that was true fiction, something that involved world-building. It’s almost like The Sims, you know? I like making something from scratch and having to ask myself if it’s believable. It really makes me question my own reality.

It’s probably somewhere in between Marvel comics and The Haunting of Hill House. I read a lot of stories and mythologies about psychics in preparation, but they never behave in the same way–like, there’s a wide spectrum of what they can or can’t do depending on the philosophy of who wrote it. I mostly wrote it because of a fight I got in with some of my family members. I was kicked out of my grandmother’s 92nd birthday party because they said that my books did a disservice to my father’s memory. I was like, I’m the best thing that guy ever did, motherfucker. [Laughs] So I wanted to explore unspoken family tensions, like, when you know something fucking crazy is going on and no one’s saying anything. When your mom asks you to pass the potatoes and it’s this very charged thing, you can hear in her voice that something is going on.

POLLOK: Going back to Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt, I’m curious about the way you use genre there–it’s sort of poetry, sort of autofiction, sort of memoir. What drew you to that format?

PURNELL: I’ve always wanted to write poetry. But poetry is so weird. They always want you to have an MFA to write poetry. I had already written seven books before I even started with poetry. Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt is very influenced by beatnik literature in the Bay area, but at points it just felt like regular fiction or autofiction. Like, I was really in there having to defend my reality at every point. The poetry is like a billboard–it gets the slogan across, but you have to be precise with such a small word count. I think what I liked most about writing poetry was the challenge.

POLLOK: What do you see as the broader themes of your work? Do you see anything similar across books?

PURNELL: Triumph is definitely one of them. 100 Boyfriends I see as being about a boy or a group of boys who have never said no to anyone. Criminality is huge for me. Being a suspect is something I have no problem with. I’m concerned with innovation in language, I like conveying the feeling of what it’s like to be washed over by a bunch of bad feelings all at once. It’s a hard thing to do, you know.

POLLOK: I like how you don’t step back in your writing. You don’t shy away from the truth.

PURNELL: I couldn’t step back if I wanted to. I hate criticism of my work that comes from, like, some writer who’s sitting cozy on their IKEA couch in Germany. People like that have never grappled with sexual danger a day in their life.

POLLOK: Some people, for whatever reason, always feel like they have the authority to comment. Even on things they don’t fully understand.

PURNELL: I took a class on writing criticism at Berkeley and the idea was to meet something where it’s at. Too often, the worst critiques I’ve ever gotten have been the opposite of that–just obliterating my work into a bunch of sex stories. There’s so much going on in my books, there’s boys that are getting married, there’s boys that are taking care of their lovers that are addicted to drugs, there’s boys that are winning against their own addiction. I hate the type of critique that’s like, someone picks up an orange and instead of describing the orange, they start explaining why the orange is not an apple.

POLLOK: Literary critics can be evil and reductive in a very plain way. What are some positive responses you’ve received about your work? Whose criticism do you like?

PURNELL: Do you know who the biggest group of people who hit me up about 100 Boyfriends are? Straight white women, usually in their mid-30s to mid-40s, will come up to me all the time saying they totally understand this character, or even that they’ve been a certain character. Those moments for me are always like, wow, have I actually written something universal? I’m honored that white women can see themselves inside these characters. Obviously, if you write a story about how a hundred men ain’t shit, who’s gonna understand but women, you know? [Laughs]

POLLOK: That reminds me of Torrey Peters and Detransition, Baby–she dedicated it to cis women who were getting divorced.

PURNELL: I’m always curious about who we identify with and why. That’s a powerful instinct for me as a writer.

POLLOK: You grew up in Alabama before moving to Oakland, right? What’s a bigger influence on your writing–the Bay or Alabama? I’m also curious about what it was like to grow up in Alabama.

PURNELL: It was so many things. I went to school in Huntsville which was the engineering town. I was studying theater of the absurd and improv the whole time. It was groovy. If I’d gone to school with my cousins the next county over, I probably would still have a Southern accent and never would’ve left Alabama in the first place. There was a lot of diversity considering it was Alabama. There were the kids of Klansmen, like, in school with me–an insane mix. Redneck boys with confederate flags on their trucks blasting Tupac.

I had aunts in Harlem so a lot of my cousins grew up in New York. I can’t imagine growing up in a concrete jungle like that, there’s always something disorienting to me about the New York landscape. The Bay Area is very landscape-driven–no matter where you go, there’s mountains and there’s water. I’ve always been a little scared of the dense thicket of New York because I can’t orient myself with so many buildings.

POLLOK: I’ve been dying to ask how you feel about sluttiness. Your books are about sex. Time to dig into the real meal here.

PURNELL: I’ve always been interested in writing about humanity and sex. I’m curious about the way sex returns our humanity to us. It’s kind of the ultimate way human beings communicate. There’s so much about sex that isn’t sexy, it’s as normal of a thing as having to brush your teeth. A lot of what I write about sex could be considered anti-erotic. The status of sex as a normal biological mechanism can warp our perspective on what it really is. I’ve noticed at certain times in my life when I’ve gotten sober from drugs or stop drinking that food and sex become a vector of obsession for me.

When I first moved to the Bay Area, there were obviously a lot of gay men older than me who were around in the ‘80s and ‘90s who had completely stopped having sex because of AIDS. It’s interesting to me how you have so much energy to have sex in your 20s but what sex means to you really changes as you get older. I can relate because, when I was younger, I would meet these guys where I was like, if he doesn’t have sex with me right now I’ll die. As you get older that feeling leaves you and you’re happy to just have sex. The meaning changes.

POLLOK: Family is another running theme in your work. How do you feel about incorporating that element into your books?

PURNELL: Family’s funny. In my new book I wrote a poem that’s all about how if I had a time machine I’d kill my parents. [Laughs] We go to therapy and we find new ways to blame our parents for everything–I started thinking recently about how my parents were raised by the Silent Generation, you know? Their attitude was like, if something bad happens to you, never talk about it. So it’s like, sure, my parents were strict, but they weren’t as strict as their parents. They didn’t have the access to all the knowledge and language that we have now. It’s funny to me that computers were literally a dream that they had and now we sit on them all day. Now I can literally talk to anyone in the world and hit them with a barrage of psychobabble about all the minute inconsistency in our behavior and all this type of stuff. I try to give them grace with all that now. Especially watching the world around me change, going from 20 to 42, I can only imagine how they felt. I mean, my dad didn’t even go to school with any white people. And now he has a black gay son who’s into punk rock. My dad is still like, scared that white people are going to poison me with veganism.

I think being queer adds a new element because life for us is so much about our chosen family. The friends we choose to get old with are lifetime partnerships. For us, that is our real lives–our nuclear family. I live with three other middle-aged bachelors who make art and it’s fun. I used to wonder if I was a loser because I never found someone to have a child with and I never had a normal life. But then I’ll be sitting here with my other artist friends and we’ll just be smoking weed and watching Dune and I’ll realize some dad with a bunch of kids could never do this.

POLLOK: Sometimes I feel really mad at my family but then I realize it’s only because I love them so much.

PURNELL: [Laughs] Thank you! That’s exactly how I feel about it. Of course they’re gonna fuck you up in some ways. But you have to remember they gave up their entire life just to have you around. I think about that all the time with my mom–I think about certain ways she was mimicking the patriarchy, or being poisonous. I’d be like, that’s not cool. But I have respect for the fact that the patriarchy is what did that to her, how is she supposed to not mimic at least some of what’s happened to her? At the end of the day, I give her a pass because I can’t even imagine what she went through being a lone single woman that was so smart in the world of 1979 in Alabama as a secretary.

POLLOK: Another running theme in your works that I wanted to talk about is trauma. How do you navigate trauma in your writing?

PURNELL: There’s one line in Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt where I talk about how we all just coexist with trauma. Some people accuse me of making fun of it or diminishing it. People have given me a hard time about my humor in the past. They see it as anti-intellectual or deflective, but it’s just the reality of how I process traumatic experiences. I’m scared, I’m disgusted, maybe I’m also cracking a joke–it’s all happening at once. Literature gives you the illusion of order because it puts all your thoughts in a list. The reality is that all of your thoughts and feelings are usually happening at once. Walking around and expecting not to be traumatized is like walking into the rain and expecting not to get wet. After the fourth or fifth or 15th or 27th traumatic thing happens to you, you eventually just put it into the file folder of your mind as things to be dealt with and you move on.

Everyone develops psychic armor in reaction to trauma as they live in the world. I’m someone who decided a long time ago not to kill themselves. It was a long decision for me, when I was partying really hard and drinking really hard, to make a serious decision not to kill myself directly or slowly. Since I’ve already made the decision to live, I have to find a way to coexist with my trauma. I’ve learned how to do no harm to others and to minimize the harm to myself. It’s a lesson you spend your entire life learning.

BRONTEZ PURNELL is a writer based in San Francisco. His latest novel, Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt, is available now everywhere books are sold.

TESS POLLOK is a writer and the editor of Animal Blood.

← back to features