PUPPY LOVE

Gideon Leek

It was on the long drive out of the city, on a cold foggy Friday afternoon. Traffic moved in stops and starts. The clouds of coming rain raced ahead. My wife had called me earlier, she wanted to talk. Something about her feelings, her aspirations, herself. She said it’d be better in person. The couple’s therapist had told us to always talk in person, about the big things that is. Our worst arguments started with texting. Some initial misunderstanding, emerging from brevity or brusqueness, that rooted itself so deeply that, by the time we got to arguing, the argument had become larger and worse than it ever initially had been. So we’d made it a rule don’t start fighting, don’t even explain the issue. Wait until you’re at home together, then talk.

The rule caused new issues for us. Like the time my mother-in-law had called, yelling at me about being late for dinner, and I had waited to tell my wife until I was at home. By then the dinner was over. My mother-in-law had a hard time understanding that I was only following the rule. Or there had been the time my wife had gone on a work trip, with her boss Chris. He’d made a move on her—trying to kiss her, dead drunk, in the Best Western business center. She’d stuck out another three days of the trip, not telling me.

The couple’s therapist was sympathetic. He’d said, “You must be practical. Use your judgement. There are exceptions. Rules were made to be broken.” He often spoke in platitudes. Which was comforting. You didn’t get the feeling he knew more than you or much at all really. In his simplicity of thought, he had a sort of divine neutrality. We trusted him completely. So my wife and I agreed to follow the rule within the rule: If something is urgent, anxiety-inducing, or important, we can talk over the phone, as long as we both feel we can stay calm. I was talking on the phone with my wife, following the second rule, when the car rear-ended me.

“You don’t have any friends outside of this relationship. You don’t have any hobbies. You don’t have any interests or dreams. All you have, or seem to want, is me—and you resent me for wanting more for myself.” She had gotten that far, when the Range Rover sent me spinning across the shoulder and into the guard rail. My bumper crushed into itself like melted ice cream. The air bag knocked my glasses into the back seat. My wife’s voice continued through the crackling speaker. “We used to go out dancing. We used to go to parties. We used to see live music. Now we don’t. Not ever. Did you ever like those things? Was that all just some elaborate mating ritual, because you were too scared to confess all you like is pizza and sitting down?”

I turned off the car. Her voice disappeared. From behind me I heard barking. I unbuckled myself and pushed the bag down, gas hissing out the sides. The driver’s side window had cracked and the rearview mirror was gone. From the backseat, I pulled my glasses. The right lens had popped out. Behind me the Range Rover was parked, hazards flashing. It didn’t have a scratch. A middle-aged woman was squatting next to it her face pressed up to a large black dog, who she was comforting. “Good boy, good Captain, that’s my good Captain,” she said as the animal nuzzled her. She did not seem to notice me. The dog’s tail was wagging, his tongue lolled happily. I wiped a streak of blood from my forehead.

“Hello?” I said, wondering if she was in a daze, half-presented or half-confused. Her head whipped around, her eyes angry and small. The dog growled. “I hope you’re proud of yourself,” she said. “You’ve nearly crippled Captain.” The dog lifted his back ankle tenderly.

“Excuse me?” I said, furious, holding my hand out to the wreckage. “You hit me. Look at my car.”

“You were out of control! Accelerating and slamming the breaks, like a mechanical bull.”

I reached for my phone. This woman was crazy. The time had come to call the police. “Don’t you do that,” she shouted. “If anyone’s calling it should be me. You could’ve killed me and nearly killed poor Captain.” She paused. “I bet you were talking on the phone.”

I put my phone back in my pocket and took a step towards her. The dog crouching, ready to pounce. “Have you ever noticed,” I said. “That those who love animals always seem to hold people in proportionate contempt? Here I am, bleeding, wounded, my car destroyed and all you can think about is your big stupid slobbering dog, without a scratch on him.”

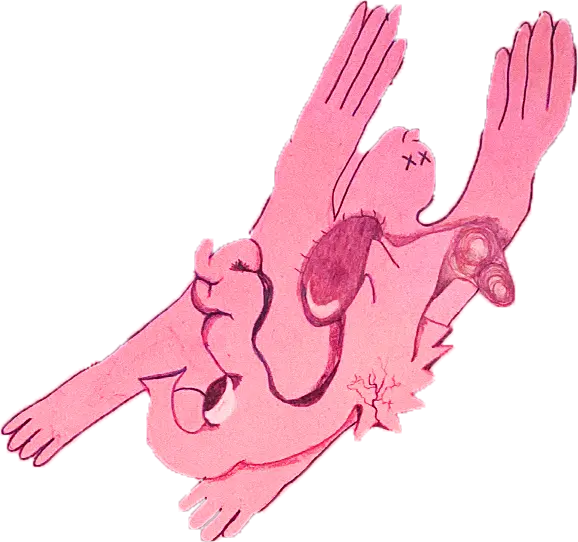

The dog leapt at me, bounding off his powerful uninjured ankle, his teeth like forty knives, boring into my fleshy middle. We fell to the ground, rolling on the gravel. I beat him with my fists, it was helpless; he wouldn’t let go. His owner cheered, “Kill him, Captain. Kill the dog hater.” Rage and pain had nearly blotted my vision, but I made out a shard of glass on the asphalt—broken off from my driver’s side window. The dog scratched at my reaching arm. Then, in an instant it was over. His throat was cut, blood soaking my face. A piercing wail came from the woman. In the distance, I heard a siren. For what seemed like an eternity, I lay there under the weight of the dead dog. I wondered why, in a world full of people like this, I needed friends outside of my marriage.

Above me, there was the loudest noise I’ve heard in my life, like a firecracker being shot into a boom mic. I almost blacked out from fear. My ears ringing with the echo of the bullet, I dimly heard the woman. “You dog killer. Captain was too good to chew on your bones.” She leaned over my face and leveled the gun from a foot away, closing her right eye to aim. Weakly, I reached an arm to push at the barrel. In slow motion, I watched her fall. I leaned my head to the side and saw that there she was, with a bullet in the head.

I spent an hour at a Westchester police station. Giving my statement to the cop who had iced her. She was crazy. She sicced her dog on me. She was going to kill me. She wrecked my car. He calmly nodded along, promised to back my insurance claim, and sent me home. In the bathroom at the station, I was alarmed by my lack of injury. The dog had barely broken the skin, the gunshot had missed, the bleeding wound from the crash had only been a nosebleed. I looked curiously whole. Sheepishly, I drove home.

My wife was sitting on the stoop when I arrived, her eyebrows quivering with suppressed rage. I held the police report tightly in my hand, like a lazy child trying to get out of gym.

“And where were you?” she asked me.

“There was an accident,” I said. “If you’d just—”

“No. No. No. There’s no excuse. I’ve been waiting for hours. I’m not going to stretch my imagination to understand. I want you to be sympathetic to me. I told you hours ago, that I wanted to talk. About some actually important. Something that concerns us both. And I waited. I sat at home waiting so we could talk. Instead of going over to Martha’s for dinner. Or going to Pilates with Isabelle. Or going into the city for a play with Angie. No, I chose you. I left my whole night open for you. And you know what that was? It was a waste. You couldn’t even be bothered to show up.”

I walked past her into the house, leaving the police report out conspicuously on the table. Maybe, in a later, calmer, time, she’d look at it.

“I’m sorry,” I said, hopefully. “You don’t have to believe me, but I really tried to be here.”

“That’s right. I don’t have to believe you.”

“You don’t. But I’m here now. What was it you wanted to tell me?”

She hesitated, unsure, her grievances wrestling. “We will discuss your disregard for my time later,” she said. Then, she began: “You know how there’s this imbalance between us? Where I have this rich social life, and hobbies, and passions, and you don’t do anything?”

“I’ve heard you mention this,” I muttered.

“I think that maybe it could help if we did something together. A big joint undertaking, something we could both work on and grow from and meet people through.”

I nodded. I was confused, touched. This was unexpected. “That’s very thoughtful. That’s really lovely. What did you have in mind?”

“Well, you know my friend Angela? Her dog just had puppies—"

Gideon Leek is a Brooklyn-based writer with work in The Village Voice, Los Angeles Review of Books, Cleveland Review of Books, Screen Slate, The Harvard Review, and Public Domain Review.

← back to features