LITTLE DIGITAL PRAYERS

Maya Man

My natural inclination is towards a tone of irreverence, but I have a critical perspective on the content that I consume. I’m in an ambiguous position…in relationship to the digital manufacture of desire. I’m curious about what the next decade [online] will look like.

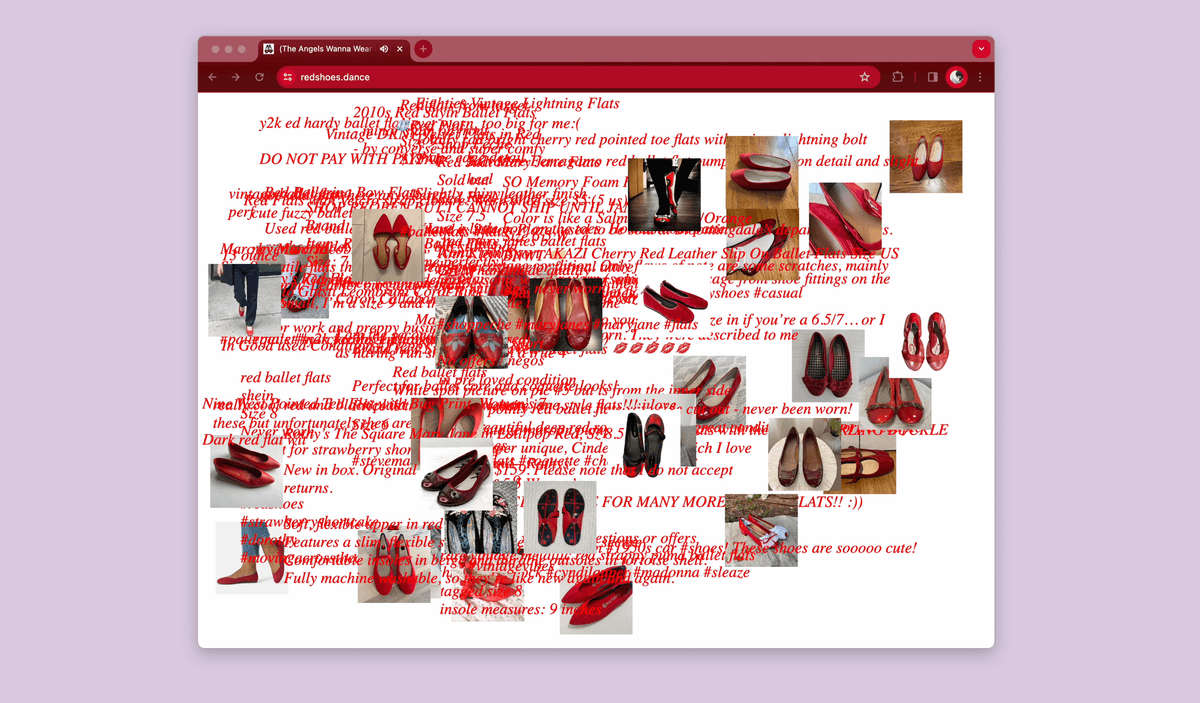

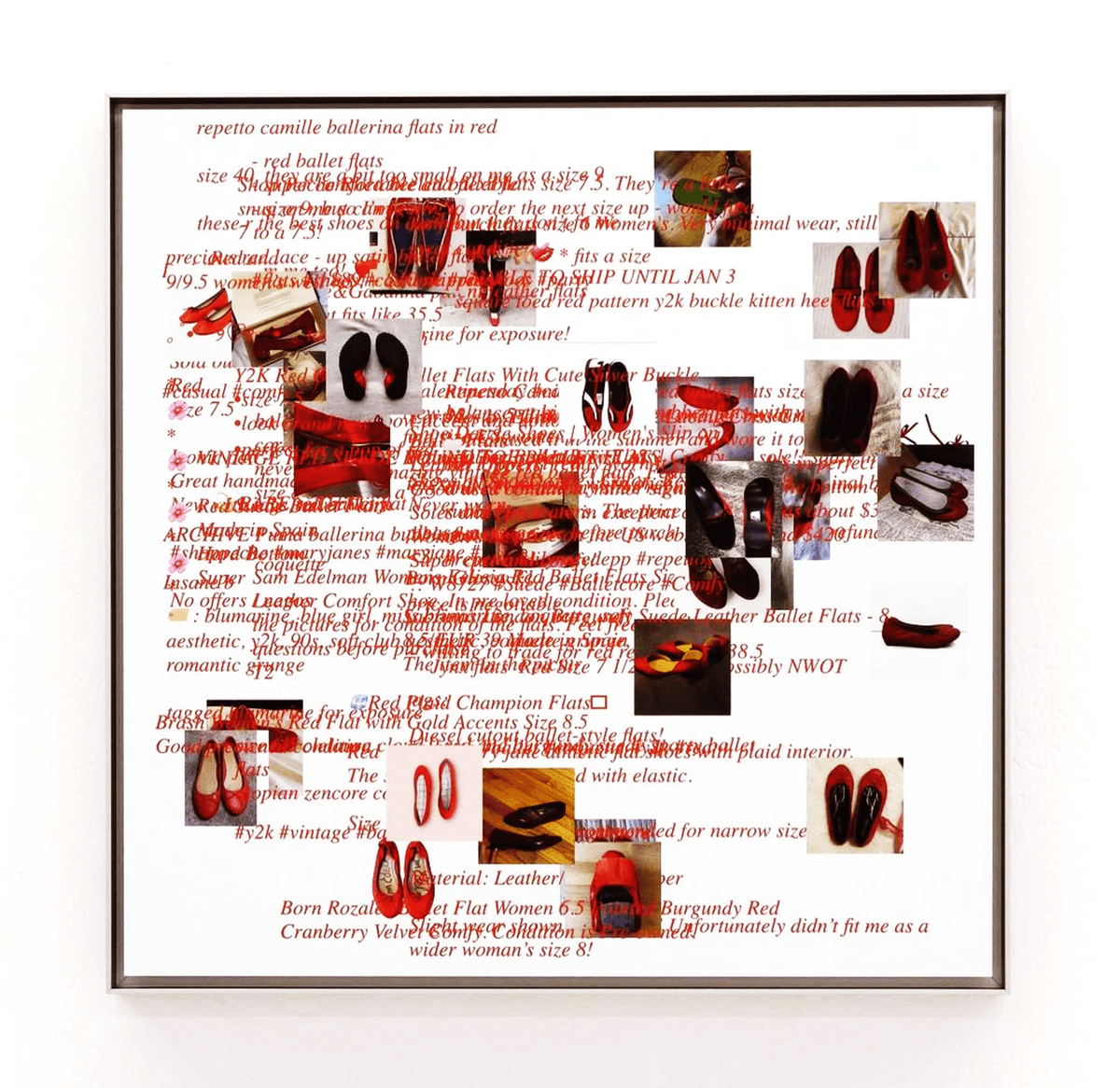

TESS POLLOK: You’re a visual artist who works primarily in digital mediums using data, procedurally generated images, and algorithms to explore human life and the online. I wanted to ask first about your upcoming digital solo exhibition, (The Angels Wanna Wear My) Red Shoes, which is opening at HEK (virtual.hek.ch) on March 7. It’s about fairytales, Depop sellers, and the manufacture of desire?

MAYA MAN: I’m really excited about it, I’ve been wanting to do a piece using data scraped from Depop for a long time. The concept for the exhibition came out of a conversation I had with the artist Molly Soda where we were talking about ballet flats and she mentioned the Hans Christian Andersen fairytale The Red Shoes, which tells the story of a young girl who intensely desires these gorgeous red shoes, finally gets them, and they curse her feet and make her dance to death; it’s a cautionary tale about covetousness. But this fairytale in particular has been re-performed throughout the last century in many different ways by many different artists–probably the most famous is the 1948 film The Red Shoes, and there’s also a Kate Bush album called The Red Shoes–so the exhibition takes its inspiration from the original Red Shoes fairytale and its various iterations to explore the ecosystem of Depop shopping. Something that really fascinated me about The Red Shoes is that, across all these different versions, the young girl is almost always sold the shoes by some sort of merchant or businessman, but that’s not what’s happening on Depop. Most of the sellers on Depop are themselves young girls who bought the red shoes somewhere, and now they’re re-performing their own desires in the way they photograph and curate these posts. So it speaks to the simultaneous manufacture of desire inherent to the creation of content on Depop that I wanted to collage together.

POLLOK: I think you’ve honed in on how this fairytale has transformed in contemporary times, specifically on how, historically, men or a businessman figure would lure a young girl into some performance of girlhood, but over the internet, girls are able to do it to one another.

MAN: Definitely. I feel like I’m always in a very ambiguous position with my work because, on the one hand, I love the internet and pop culture in a very earnest way, and on the other hand, I have this critical perspective on the content I consume daily. With the manufacture of desire on Depop, there’s something both scary and beautiful about the way this content is so intimate and personal but also so transactional. The photos are in someone’s bedroom, as opposed to the sterile photos you would get from a brand website, but at the same time, they’re filtering these images through the persona of a salesperson with hashtags like #lilyrosedepp or #coquette–capitalizing on the breadth of knowledge they have of these trends because they’re so deeply embedded in the terrain of consumerism. But there’s also this quality to the writing that feels so personal, these posts walk the line between being overtly anything.

POLLOK: It’s interesting that you say that it scares you, because I was wondering what your position on this phenomenon was. Are you just curious as to why this is happening? Or are you taking a critical lens to how all of this is a “cautionary tale” to avoid consumerism and girlhood?

MAN: I’m an obsessive observer. This is something I think about all the time. I’m really interested and curious in these reproductions of girlhood even as I filter them through myself, but I try to avoid ever having this hyper-critical attitude where I’m performing as an artist as if I’m outside of this experience and looking down on it. It’s important to me to stay embedded in it, because the heart of this work and the book I put out is critical–a lot of the specific studies that happen in these pieces represent a major issue on living on the internet, this hyper-paced and immediate gratification universe.

POLLOK: When did you first start coding and how did that inform your artistic practice?

MAN: I started coding the summer after high school because my mom was, like, “Oh, apparently, people who love math love programming.” I went to a summer programming camp and we all made personal websites and I was immediately hooked because of the instant gratification of it all. It had the aspects of logic and problem-solving that I was used to as a math student but the output and design of a website could make it all real. In college, I studied computer science and media studies. I met more and more artists who used code as a medium, and that really inspired me, specifically Lauren Lee McCarthy, who taught me to think about technology systems and how artificial intelligence operates. Her work is very tech-critical. She was the first person who showed me that work about the online doesn’t have to be just shiny visuals, it can be real. I’ve always been obsessed with making things online–videos, websites, blogs–and at that point I just realized you could translate any or all of that into web-based art.

POLLOK: Something you acknowledge in the press release for your new show is the “thousands of think pieces, Tweets, and TikToks,” that have already theorized on the hyper-accelerated pace of consumer culture due to micro-trends. What was the value in considering these objects individually?

MAN: I think about this all the time. We read so much writing online that’s about the flattening of the algorithm in this very abstracted way. Nothing is more emotional to me than seeing specific instances of this represented online, seeing the actual material objects that are the product of these trends emerge and layer this piece. I wanted to use images from Depop because these images allow you to see the sheer number of products in this one tiny, tiny category–if you think too hard about the abstract, you lose the impact of the original image.

POLLOK: I get that. You’re illustrating for people all the individuated performances of this piece.

MAN: Yeah, and it happens so quickly because of how fast trends move. Like, even the Depop pieces I’ve published recently feel archival. And with my book, the memes feel like a relic of 2017 to 2020, more than a relic of contemporary culture now. It’s strange to mark these moments in time.

POLLOK: What do you think the hyper-acceleration of trends will do to the internet over time?

MAN: It’s hard for me to predict. I think the pendulum always swings and it’s swinging fast right now. Youth culture has always been reactionary to the norm and as it becomes more reactionary to the quick pace of trends there’s an obvious interest in divesting from that. It feels unsustainable. I’m curious about the next decade, for sure.

POLLOK: I feel the same way, it’s like watching the housing bubble burst. We’re living through a moment in the digital sphere when people want things to be more private. We talked about this in an interview we did with Biz Sherbert, who also wrote in your book, about how people in the early online, in the ‘00s and ‘10s, wanted the most friends on MySpace and Facebook to seem more popular, but now people have receded into the territory of Depop and Discord to have more insular social groups. But it’s confusing, because people make these critiques all the time.

MAN: Exactly. It’s hard for me to tell what’s real when the critiques of the internet and online culture fundamentally resemble, you know, critiques of television when television came out. I think the internet has intensified these concerns in an extreme way, but I think because we’re on an upward trend with use of the internet, the reactionary comeback is going to be hard and come in a larger way than ever before. It’s hard to imagine. I don’t see things continuing the way they’re going because of how dystopian it all feels.

POLLOK: Do you think about the private future of the internet? What about Web3, which aims to decentralize the internet? The emergence of Web3 responds to this desire to negate oversharing and to stop the oversaturation of information, especially news information.

MAN: I have so many thoughts on this. The dream of Web3 is that it would distribute the burden of self-promotion and presence away from artists, which may or may not be true, working in practice. I’ve been watching the Web3 space for awhile and I think it’s a little bit unrealistic about what it can accomplish. The rhetoric around it is idealistic. What I’ve been seeing is people building centralized platforms on top of the blockchain that re-perform a large part of the Web2 elements that everyone was so critical of initially. There are aspects of Web3 that I think are good, like smaller group chats and tighter knit communities, but what kind of start-ups are people founding in Web3? I’ve found that small spaces are meaningful and valuable, having a backchannel to social media platforms is important and amazing. I’m feeling a big pull to return to in-person hangouts. Basic things, you know?

POLLOK: Absolutely. I think there’s something a bit ponzi scheme-ish to the architecture of Web3 because people who don’t buy into this absurdist concept that it’s going to liberate the internet, well, they’re out of it. But it’s hard to say, because with NFTs, you know, people said NFTs were nothing and they’ve built a self-sustaining infrastructure, thus far. Maybe Web3 will turn out that way. But the logic of it has always slightly eluded me, it doesn’t clearly address the problems it posits to solve.

MAN: 100%. On the surface, I’m, like, I’m down for a distributive internet, one that’s de-invested from the centralization and monopolization of Web2. But when I try to dig into it, like, how does it work? It doesn’t make sense. I’ve been reflecting on the NFT universe in terms of its promises of increased autonomy and independence for artists–at least in the NFT universe, people reacted to the contemporary gallery model that art functions on, the same can’t be said for Web3. Very few artists end up being successful in the NFT space, and I think even less so with Web3.

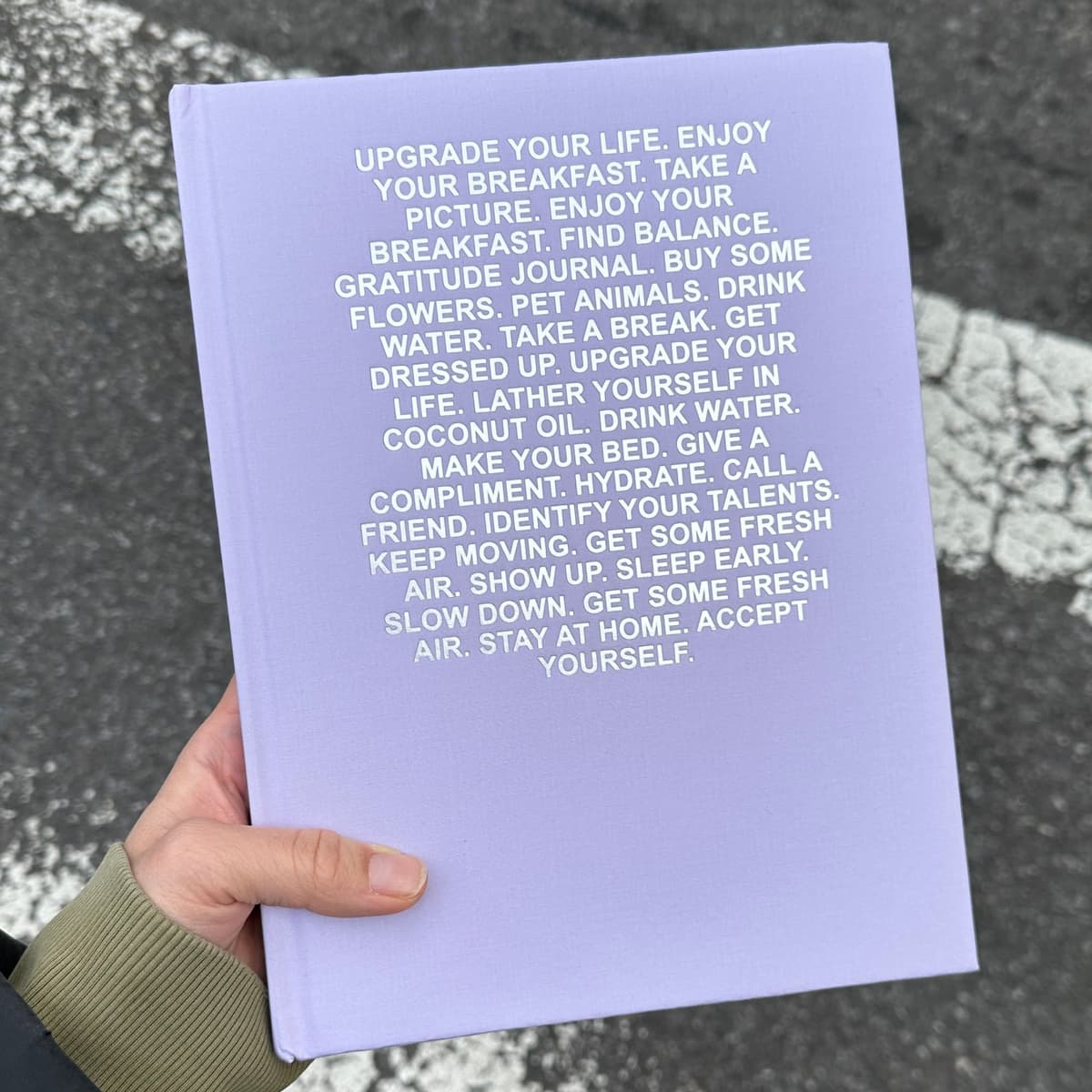

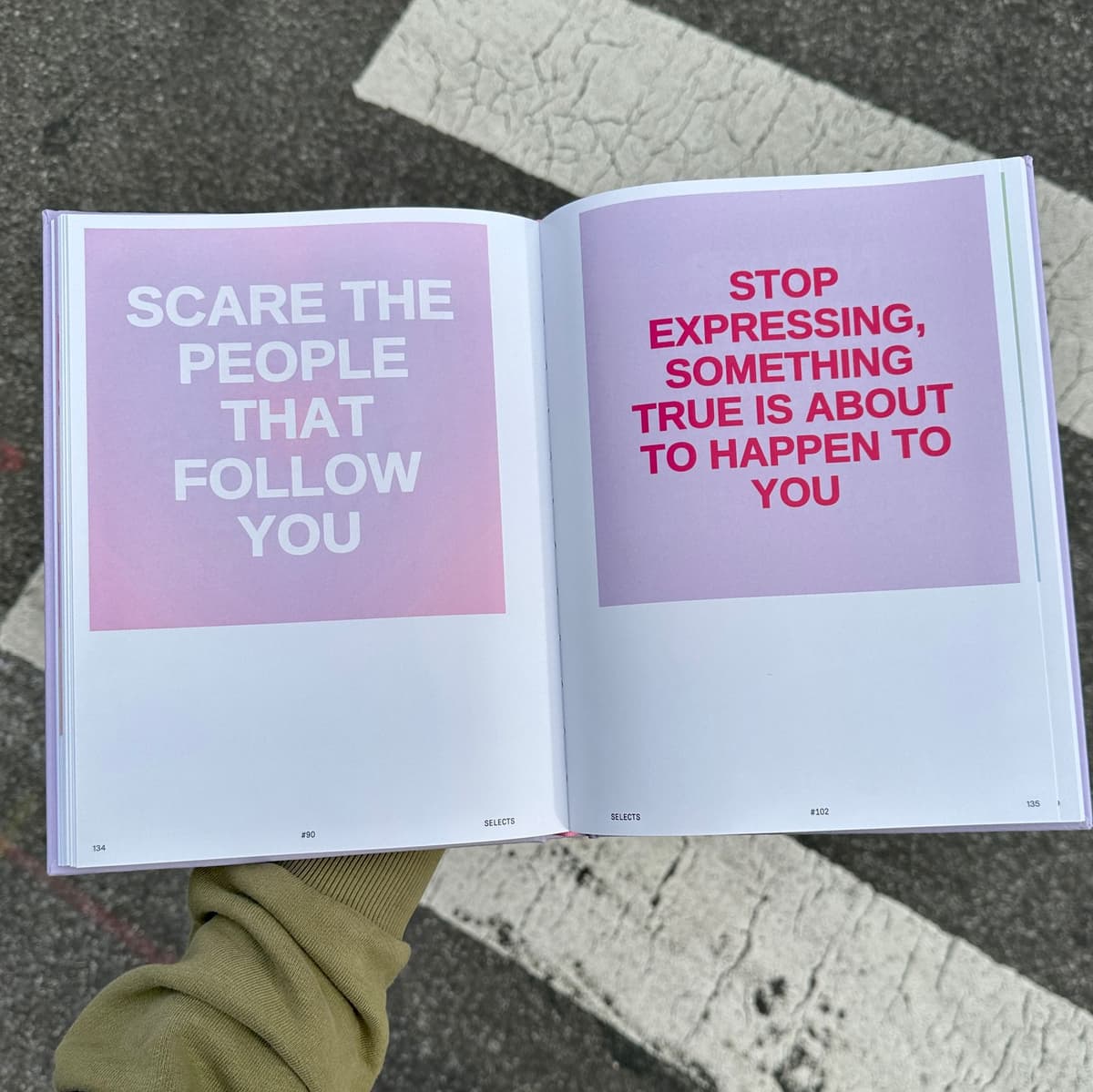

POLLOK: This segues very beautifully into my question about your book, FAKE IT TILL YOU MAKE IT, which is also an NFT series. You released a book of procedurally generated memes revolving around “self-care culture.” What was it like to comment on that, and how did you do it?

MAN: Yes, it’s an NFT series released on ArtBlocks, a generative art platform. I feel like the project has a double life, for sure. Because it’s very embedded in the NFT world and the Web3 universe, but people bring it up in arts writing or on Instagram without knowing about the NFT premise of it. It’s very feminine compared to what was being generated of NFTs at the time. But most people have come around to it, and when I post these graphics on Instagram, it’s interesting because people who have zero knowledge of its existence in the NFT space really respond to it.

POLLOK: Well, I have aesthetic beef with the concept of NFTs–I just think they look bad. I don’t understand where the concept that they were going to be avatars of us came from. What’s the unifying belief beneath these things? That your digital avatar is going to go on digital adventures for you?

MAN: Yeah, it’s been difficult to have stake in this space. I’m critical of the popularized aesthetics of the NFT as well. There are PFP projects like Bored Ape, ugly avatars which are unfortunately synonymous with what the NFT is to many people–and the majority of generative artwork tends to focus on visualized mathematics. At my core, I have a strong belief in the value of digital objects, but it’s been frustrating over the past, forever, I don’t know, because there’s no market for that type of work. As a digital artist, you can’t operate in the way that an artist who works in traditional mediums operates, because there’s no market. What’s exciting about the NFT world is that suddenly there’s a market, but it’s so shitty that artists who are interested in the internet beyond current NFT aesthetics are left largely feeling excluded.

POLLOK: Ultimately, it was venture capitalists who pioneered the NFT space–people with stoner brain who were, like, “What if there was digital space for art museums?” None of the internet or post-internet artists I’ve worked with have ever had any involvement in the NFT space. So internet artists got sold out of this ecosystem, as if it’s been made for this new class of people who don’t even exist yet.

MAN: Yeah. There’s no name for what’s happening right now, but most internet or post-internet artists I know have been able to find success through some means of physical production. Translating their practice into a traditional vernacular worked for them. I think for a lot of artists, it makes sense to collaborate with the world of NFTs, but to do so you have to align values-wise and concept-wise with this entire framework that may or may not not make sense to you. It’s being presented as the default option if you want to have a market for digital work–I’ve felt really frustrated by the in-between-ness of what the NFT world offers and what I felt was there for internet and post-internet artists. Maybe I have a more romantic view of that world, but in the future I would love to produce curatorial projects where I could bring together digital artists and kind of, like, siphon them off from the NFT ecosystem.

POLLOK: There’s an amazing article in the Los Angeles Review of Architecture about LACMA’s failed attempt at a virtual museum and how accidentally hostile they’ve been to the digital infrastructure of the art world and NFTs. It’s funny to watch, like, NFTs try to capitalize on the digital space, and art museums try to capitalize on the digital space, because it feels like neither one of them is getting it quite right.

MAN: Most internet artists I know have fuzzy boundaries between each other, but there’s no external external institution that’s governing us or our associations with one another–there’s good stuff being done, but I’m not sure how to create the context of it to be defined more.

POLLOK: What internet artists do you admire?

MAN: Ann Hirsch’s work has always been really inspirational and useful for me to study. It’s been amazing to collaborate with her on some projects. We have an event at MOCA coming up at the end of this month. Molly Soda’s work, I’ve loved watching it evolve over the years and the way she talks about the internet is really sharp in a way that I admire. There’s also this artist Michelle Ellsworth, who comes more from the dance world, but she’s made a bunch of different websites as a part of her practice–her work has been emotional for me to engage with. There’s definitely a lineage of artists who have worked with code and software, like Casey Reas, who co-created Processing, this software that helps artists work with code. Seeing the way that he talks about software has been inspiring–there’s a lineage of artists who work with code and there’s a lineage of artists who work with themes of femininity and the online as a concept but don’t necessarily work with code, and those are the lanes I’ve always looked to.

POLLOK: What made you interested in the intersections of girlhood and the internet?

MAN: Genuinely, it’s always been a thing of personal obsessions. I’ve been embedded in the culture of girlhood since I’ve been on the internet. It was very natural to me to make work on that and reflect on that. Even when I go back and read diaries from middle school, before I was interested in art in any way, I’ve always had this interest in the guilt and shame that hovers around girlhood and the internet and posting; I always describe it as love-hate because I love sharing online. But I’ve always felt ashamed of that instinct, in a way, as well. My work is the way through that feeling.

POLLOK: Are you a neutral observer of these phenomena on the online or are you critiquing it?

MAN: I’m definitely a critic. I feel pretty negative about it. I think my natural inclination is towards a tone of irreverence and I’ve thought about trying to change that about myself, but I can’t. The exhibition and the book are both inherently critical. But something I found, working through the book, is that sometimes the algorithm would output these phrases that I did find inspirational or helpful, sort of pseudo-religious, so I understood how people could relate to banal positivity in this way. They’re sort of like little digital prayers. As I’ve gotten older, you know, I initially thought of the project as more cynical and critical, but I’ve come to embrace the parts of it that can be actually inspiring. I just don’t think we should derive our life’s entire meaning from pink infographics.

Maya Man is an artist based in New York City. Her digital solo exhibition with HEK, (The Angels Wanna Wear My) Red Shoes, will be online March 7 at virtual.hek.ch. Man is also the author of FAKE IT TILL YOU MAKE IT, available from Heavy Manners Library.

Tess Pollok is a writer and the editor-in-chief of Animal Blood.

All images courtesy Maya Man and HEK.

← back to features