FREEDOM

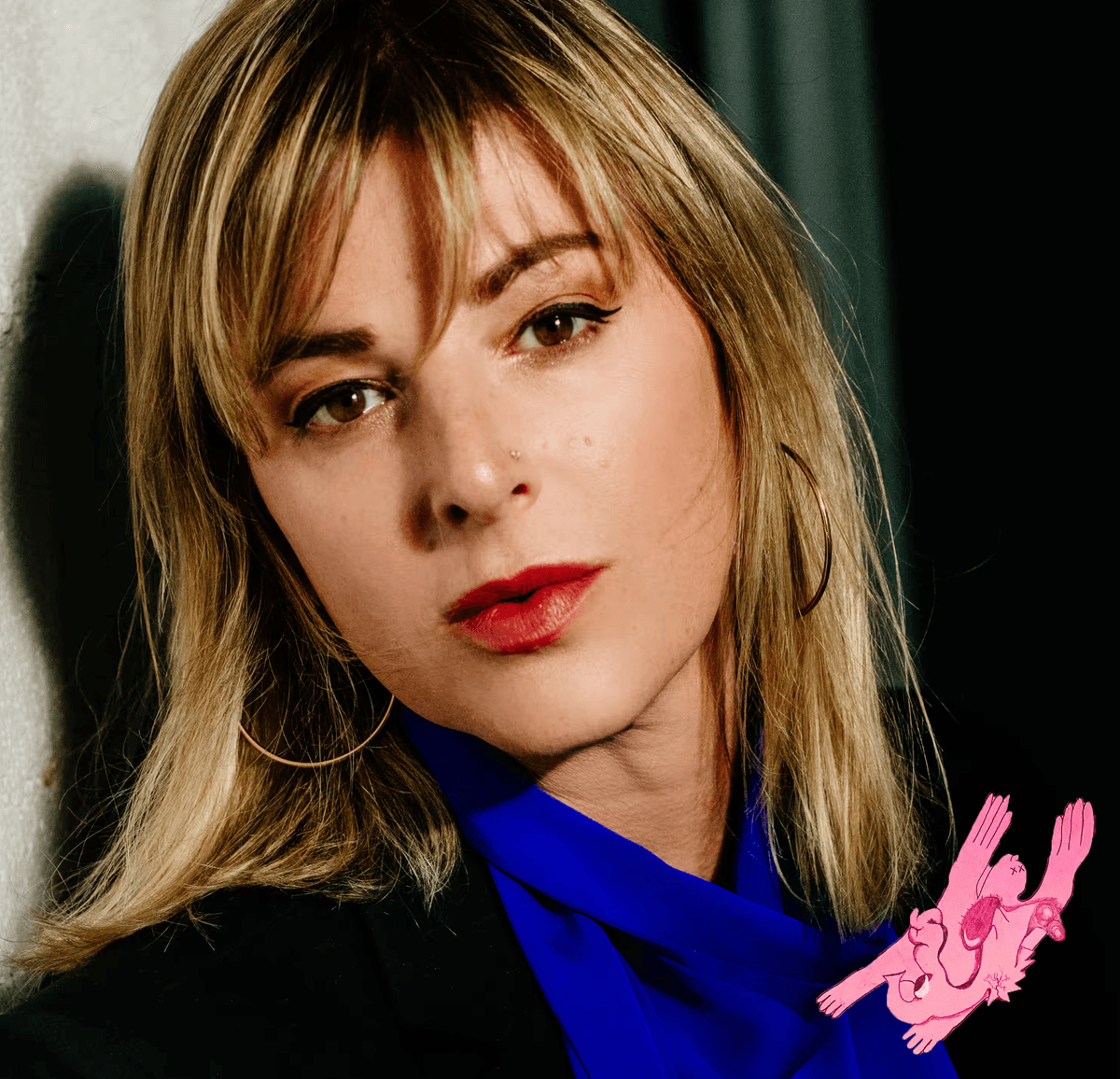

Torrey Peters

Sartre said it’s fiendishly difficult to be free. Freedom is all about context. It’s not that one day you find your freedom and are suddenly free of all constraints, it’s that you learn how to make a strong and active approach to self-determination within life’s constraints as you recognize them. Stag Dance is about freedom…about helping people recognize how they get trapped in the dichotomies of their own lives.

TESS POLLOK: You’re the author of Detransition, Baby, a powerhouse of a debut novel that was longlisted for the 2021 Women’s Prize for Fiction and won the 2022 PEN/Hemingway Award. This year, you’re back with a new book of short stories (and one novella!) called Stag Dance. There’s so much to say, I almost don’t know where to begin: Stag Dance is an insurgent, eclectic collection of stories on sex, gender, power, and desire–from post-apocalyptic speculative fiction in “Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones” to almost magical realist historical fiction in Stag Dance. I want to talk to you about the pieces in this new collection and your approach to craft in general, but before we get ahead of ourselves, let’s start with the new book. What drew you to this presentation for Stag Dance? The stories huddle around a few shared themes, but there are little common denominators otherwise.

TORREY PETERS: I like to meet readers where they are and in the service of that I like to play with time and genre. For example, the timeline of Detransition, Baby is essentially the timeline from Pulp Fiction–it’s a double timeline with two arcs, one in the past and one in the present, superimposed on top of each other. It’s also Westworld and any number of other prestige TV dramas that people are watching. My interest in genre really stems from what it can do for me as a writer and how it can help me connect with my audience. I have a healthy sense that I’m not a mid-century writer. I’m not writing for people who grew up reading Faulkner. Meeting readers where they’re at is important to me. I think Stag Dance understands that the contemporary reader is more in tune with the Twilight movies and the Marvel cinematic universe than they are with As I Lay Dying in terms of how they read narratives. Structurally, I think of Stag Dance as a huge dance movie with all these numbers. It’s Carrie. It’s 10 Things I Hate About You.

POLLOK: Do you see a relationship between the genre you’re working in and what you’re trying to say with each work?

PETERS: That’s an interesting question. I think I tend not to. To me, there’s no qualitative difference between the homosocial yearning of upper class British people in A Separate Peace to the lustful teenage yearning of a high school girl for a vampire in Twilight.

POLLOK: I felt that many of the stories in Stag Dance were speculative to some degree, even the ones that weren’t outright science fiction. Or, rather, you speculate on these projected extrapolations of our current relationships to love, desire, and respectability across all these stories. It reminded me of Catherine Lacey’s Autobiography of X, which also uses speculative fiction elements to provide social commentary. One of my favorite lines from contemporary literary criticism comes from Audrey Wollen’s review of that book: “Everything could change and nothing would be different.” That felt apt for Stag Dance, as well. Although the characters range from these gruff turn-of-the-century frontiersmen to these totally recognizable modern day women at a crossdressing convention, they all seem to be saying that nothing would change about us even if everything did.

PETERS: That’s funny. I do think of the speculative America that Lacey builds in that book as being, for lack of a better word, not really that speculative. [Laughs] There’s another great title in this genre, X by Davey Davis, which is about a bizarre and dystopic transhumanist future where the government deports and disappears writers and other political dissidents. Again, that made me laugh because it’s barely even speculative fiction at this point–it’s predictive fiction.

The first story, “Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones,” is so absurd it’s almost a joke. Like, what is the scene I’m setting there, a trans dystopia in which a viral pandemic forces everyone to pick their gender? There’s an irony to it because the main character, who is a trans woman, says, “I want to live in a world in which everybody has to pick their gender.” The irony being that we already live in a world in which everybody has to pick their gender and they do it every day: when they choose their haircut, when they choose their clothes, when they think about how they’re going to talk or phrase things. People take it for granted that they might not be making these choices consciously or deliberately, but they’re still aware of them and making them all day long, nonetheless. So the idea behind that story was, is a world where we all have to pick our genders consciously a utopia or a dystopia? It’s potentially a utopia, according to the trans girls. The contagion is just a conceit to invite the reader to explore that. It’s just inviting the reader into a world where doing that is making people freak out. It’s funny because they’re not freaking out that everyone is sick or climate catastrophe or anything like that. They’re freaking out over gender. I think it resonates with the Audrey Wollen quote you shared.

POLLOK: Does that position feel nihilistic or cynical to you?

PETERS: Not at all. Utopia is about facing your freedom with intention. We all already choose our genders, the only bad thing is that we all hide from that fact. If people were aware of doing it, it would actually become more difficult than it is now because you couldn’t just do it absent-mindedly or by default anymore. Sartre argued that freedom is about context, not self-determination. Freedom isn’t that you suddenly just become free and there are no more constraints, it’s about recognizing that certain constraints and restraints have been placed upon you and making a strong and active approach to self-determination within that context. Like Sartre said, it’s fiendishly difficult to be free.

POLLOK: This is all very pro-free will. I take it you’re pro-free will?

PETERS: Yes. I thought a lot about freedom with this book and with Detransition, Baby. I’m interested in freedom and I mean that in a very non-jingoistic way. People don’t use the word freedom to mean what it should anymore. I hate that I sound like a conservative when I say that, but it’s true. I’m a post-9/11 baby and, growing up, freedom meant wearing an American flag pin on your lapel and acting like an obedient, unthinking automaton. It feels like we’ve ceded the term freedom to the right since, basically, the ‘50s and the Red Scare. The way they use the word freedom feels entirely wrong to me. Again, freedom isn’t about having the right to do anything you want, it’s about intentionality. It’s about recognizing your position in society, understanding the positive and negative implications of your selfhood and desires, and figuring out how to make active choices within that framework.

POLLOK: Do you relate freedom in your work to identity and to self-determination? I agree that the word freedom has been watered down, but I see that as part of the general corrosion of language that identity politics and infighting have caused. People’s fixation on identity and language can be the most exhausting thing in the world.

PETERS: I’m interested in action over language. A lot of identity politics discourse is caught up in distinctions of language rather than how one is in the world and how one behaves in the world, which is what interests me as a writer a lot more. I don’t care what people overtly call themselves. I do care how people act and the kinds of choices they make.

I don’t think of Stag Dance as being about what’s male or female, or what’s cis or trans. It’s more about washing away the dichotomies and borders that abound these concepts than it is about investigating what’s on either side of them. There’s only four people in the entire book who explicitly identify themselves as trans and everybody else is just a person processing weird gender feelings. Again, as a writer what really interests me is the emotional building blocks that create these kinds of experiences for people. Where do people feel moments of gender friction in their lives–do you have moments where how you want to see your body or want to behave in your body is not in alignment with what’s happening around you? The feelings we share around these experiences aren’t so entirely different that we need a completely different set of languages, trans and cis, to describe them. That’s partially why this is such a genre project. I wanted to show how you can write “trans stories” in any way–Americana tall tales, teen romance, horror.

POLLOK: Who are some of your favorite writers? Did you have any person or specific work in mind when you were writing Stag Dance as inspiration?

PETERS: I go through eras. I like different schools of thought, different styles of writing, different authors. I’ll like someone and then I won’t and then I’ll rediscover them. For Stag Dance–the titular novella, not the collection as a whole–the inspiration came primarily from things I was reading and writing in my early and mid-20s. I wanted nothing to do with that writing for a while afterwards, which is funny, because when I eventually did circle back to it I had a lot more fun with the material. Something I was reading at the time that ended up being influential to Stag Dance was “Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned” by Wells Tower that came out in 2011. At the time, I read it and forgot about it. For some reason, I picked it back up during the pandemic, and was, like, “Wow, this is awesome.”

I’ve recently come around on Melville, as well. Again, if you asked me if I wanted to read Melville in 2016, there’s literally nothing I would’ve wanted to read less. In 2016, I was all about Ferrante and Rachel Cusk. But things change. I really like Melville right now and the chances that I’m going to pick up Outline again are slim.

POLLOK: I forget who said this, but: the artist is an endless child. You’re forming non-linear relationships with these works through dropping and revisiting them all the time.

PETERS: Yeah. I just re-read Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas because I’ve become interested in new journalism again. I’ve been thinking a lot about that era and how journalism related to the Vietnam War because of my fascination with how people are talking these days. It feels like walls are so built up around peoples’ intellect and ideologies that it’s become almost impossible to get any point across. During the Vietnam War, the general public was accepting what they heard the conflict from the government, and artists, collectively, went, “Well, seems like everyone is set on feeling like they know what this is. So instead of trying to persuade them with logic and facts, we’ll hit them with wild, stupid emotions.” That’s something I love about Fear and Loathing. It’s just an incredible story of two guys trying to talk about the American Dream and the specter of fascism. And the whole thing is set against the economic collapse at the end of the ‘60s, it’s just wild. It’s definitely a narrative that would penetrate the armor of what we call hot takes these days.

POLLOK: I have so many responses to your points. I’m thinking about my recent interview with Aria Dean for the LA Review of Books on her new essay collection, Bad Infinity. She writes about subjectivity and, to a lesser extent, the thought economy of hot takes as they relate to identity politics and the art world. I originally wanted to title that interview “Infinite Fun Reality Tunnels.” It’s a phrase from the UCLA professor Matthew Harris about how ideology has atomized human life.

PETERS: That feels so appropriate for a discussion of Stag Dance. Stag Dance is about honing in on the emotional truth of these experiences we have with gender and identity, not being obsessed with the cogs and wheels that make up their material parts. With both Stag Dance and Detransition, Baby, I was thinking about how people are so dissatisfied with modern life that audiences have become more open in terms of who they’ll identify with and relate to. We live in an era where straight people are open to hearing that gay people have something to teach them about the language or experiences of sexuality, or that white people are developing an interest in how the work of critical race scholars relates to their experiences as white people. I’m seeing more and more of that discourse entering the mainstream. For example, everyone was texting me about the autogynephilia scene in White Lotus.

POLLOK: How did you feel about it? People went nuts for that.

PETERS: I get it. They’re trying to play with autogynephilia but they’re getting it all wrong. My only point bringing it up is that these experiences we have with gender have really entered the mainstream for a scene like that to be on one of the most popular prestige TV shows currently streaming. Trans people have developed a language for seeing themselves that cis people relate to and are willing to adopt to describe their own experiences with sex, gender, and self-discovery. This is what I see broadly happening in our atomized culture: a deeper willingness to relate to otherness.

My whole point with writing Detransition, Baby was to look at the publishing industry and be, like, “Okay, you want this to be about queerness, you want this to be about the alternative family, you want all these things.” But these aren’t localized, itemized experiences that you can just pull off the shelf, you know? That’s what bothered me so much about that White Lotus scene. In Detransition, Baby, the book ends without an answer to the “riddle” of queerness or the alternative family, because there is no answer. These questions we have about desire, sex, and gender can’t be answered for you by a book or a TV show–you have to figure it out yourself. There’s no prescriptive answer to these things that is ever going to fit everyone or fit into our atomized consumer model.

POLLOK: Good luck getting people to do that. I think that’s a noble cause, but I’m telling you now that you’ll never get people to think for themselves. Or to do what feels good and right for themselves at the expense of what they’re told is good and right for them to want.

PETERS: The more I take responsibility for my desires, the better I feel about them.

POLLOK: I wholeheartedly agree. But you’re swimming upstream. I’m telling you people just won’t do it, it doesn’t matter how loud you shout that it’s actually healthier and actually feels better to be that way.

PETERS: Taking responsibility for yourself is important because if you take responsibility for the things you are and the things you want, you might end up having to look at what that means for yourself and the world around you. I don’t mean that in a positive representation kind of way, I mean, like, literally looking around you and asking yourself: have other people tried this? Did it work then? How can I make it work now? Is it considerate of people around me?

My work is filled with negative role models as much as positive ones. I want people to relate not only to the celebratory aspects of self-discovery but to the icky moments, as well. I love the character Krys in The Masker because she’s a character caught in the dichotomy between respectability and fetishism, as though those are the only two options. The thing is, she ends up making terrible decisions because she can’t break free of that dichotomy, which I see as stemming from historical transmedicalization, in the metaphor of the text. I presented her character in that way because I wanted people to think about how they get trapped in these dichotomies in their lives, as well. Maybe you would make a choice that she doesn’t. Or maybe you would make a choice that feels just as bad. The goal, I think, is to help people realize these dichotomies aren’t real.

POLLOK: I hate to even ask you this, but it feels completely unavoidable given the territory we’ve entered. How does it feel being a trans trailblazer who’s credited with bringing this into the mainstream? Does being a maverick get tiring?

PETERS: I don’t necessarily believe that about myself, but I know that attitude about my work is out there. I’m happy to accept praise insofar as it’s useful for marketing my work and getting gigs at international literary festivals. Books are commodities and I’m not naive about circulation. So, yeah, I’m happy with all that stuff. I just don’t believe that it’s the most important epistemology underlying my work, nor does being a radical voice for trans people motivate me to make work. If someone tells me, “You’re a trailblazing maverick who brought trans language into the mainstream publishing world,” I just say, “That’s great for getting me a gig at a literary festival in Amsterdam,” or something.

POLLOK: It’s a useful tool. I see how it’s a nice hammer to have in your tool box. You reach a lot of humanist conclusions in the book about the nature of desire and identity. It feels, for lack of a better word, productive. One thing I think all artists, but especially writers, struggle with is just the nature of the American media consumer/reader. I find that your points are very nuanced and reflect a sophisticated understanding of love, sex, and power, but, like, I have to square that with the fact that the average reader is reading your book at the same time as they’re watching news coverage of anti-trans bathroom bans. It’s all one big slurry and they’re eating with a huge soup spoon, kind of waters down the efficacy.

PETERS: I’m not concerned with efficacy. [Laughs] You don’t become a novelist for efficacy! It’s funny you bring that up because I just read a defense of humanism by Sarah Bakewell called Humanly Possible: Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope. In a broad sense, I agree with humanism, although I admire it more for its artistic effects. If I center the human in this classical way, can I succeed in producing feelings in the readers that make the world seem more enlarged? That interests me more than leveraging humanism to, for example, justify who I think should run for president. There’s a time and a place for everything and I find that art is not the place for political pontificating, in fact I kind of hate when that stuff gets misapplied and I feel like it’s that way almost constantly, now.

POLLOK: I relate to that. Stag Dance feels great to me because it feels defiant.

PETERS: I like that. Stag Dance is defiant.

TORREY PETERS is a Brooklyn-based novelist. Her first novel, Detransition, Baby, was longlisted for the 2021 Women’s Prize for Fiction and won the 2022 PEN/Hemingway Award. Her first story collection, Stag Dance, is available now wherever books are sold.

TESS POLLOK is a writer and the editor of Animal Blood.

← back to features