FAMILY PLANNING IN THE COVID ERA

Harris Lahti

The powder-blue vinyl doesn’t have an extra bedroom… The bi-level’s cedar shake are so splotchy with tannins I know no amount of careful staining will ever even them out… And as for the two-hundred-year-old farmhouse she loves so much: the wind howls through those walls as if they’d been perforated with billions of microscopic holes.

The stone cottage is a real contender. After the viewing, Maxine says she can picture us there, watching our future children playing in the yard from Adirondack chairs on the wraparound porch. But these days, Maxine can picture us watching our future children playing in any yard, from any chair on any wraparound porch in America, and I’m forced to play the skeptic, a role I have no business playing, considering the mortgage of our future house will hang solely around her name.

“What about the speeding cars?” I say. “The road is clearly a shortcut for New York commuters. Do you really want to spend the rest of our lives afraid our children will be vaporized by an SUV? I’m sorry, Maxine, but if you’re asking, if you really want to know, the stone cottage is a negative for me.”

The outfits start around this time: Maxine’s spandex and faux-leather fixation, the chain-link collars. Once upon a time, the packages that arrived at our small apartment in the village contained only meal prep kits, printer ink cartridges, and cans of Science Diet for our two small dogs; not these underwear attachments that I can vibrate remotely via an app on my cellphone.

Night after night, Maxine trots each out like: Special occasion! To which, I say, “My Goodness. My God.” I fake Grand Maul and writhe about our apartment, annoying the young librarian that shares our duplex with us. In other words, I play along; which isn’t hard, after almost ten years together Maxine’s touch has never failed to return me to a Stone Age of shapes and sounds.

Though we’ve celebrated five anniversaries together, and as many Valentine’s days; we’ve taken tropical vacations to budget all-inclusives, frequented love shacks in the Poconos with heart-shaped Jacuzzis and mirrored ceilings and walls—and when I see her floating toward me across our attic bedroom in white leather and angel wings, I know the last thought I should be thinking is: “Why this now?”

These days, Maxine leaves for work at the break of dawn, and this particular morning, when she leans in to kiss me goodbye, my half-asleep brain mistakes her blue nurse scrubs for more random lingerie and, dutifully, I attempt to pull her down.

“Off, off, off.” She twists free of my groping hands, then shakes her head at me before sinking, step by step, into the dusty attic floor until it’s just her head there, hovering above the ground:

“I have them on,” she says.

“Have what on?” I say, groggily. But then her head is gone.

For a while, I lay there fighting sleep, unexcited about the idea of shooting a signal from a satellite in the vastness of space into my wife’s vagina while she commutes down a busy highway. At another point in our life, perhaps—before the house-hunting, the decision to start a family, when the introduction of these kinks could’ve been just that, not some act of superstition aimed at the fertility Gods.

Either way, dear God, I’m obligated now. We both know I have nowhere to be today, that the painting subcontractor I work for hasn’t been returning my calls since the shutdowns.

My finger pushes, seconds pass, a minute; just long enough for me to start thinking that maybe the underwear attachment had been a joke all along.

Then, alas, a vibration: a lightning bolt and an angelic baby emoji staring back at me from my palm.

On CNN, the same static shot: ambulances pulling in and out of a hospital in Rockland, an apparent “hot spot,” that a Google search reveals not to be too

far from Maxine’s hospital, her nursing job.

On the futon, still in my underwear, our small dogs nuzzled against my bare legs, the remote heats up in my hand.

Somewhere off the west coast, a cruise ship idles ripe with disease. Apparently, ventilators are already on short demand. The curve hasn’t

flattened, a graph informs me; in fact, it’s begun to spike.

Within minutes, I develop a light cough.

Since she left, I’ve already called Maxine five times. The phone, a constant awareness in my lap. When she finally returns my call, the phone barely rings one before I answer.

“Try to stay positive,” she says, muffled with her N-95 strapped on.

“I’m taking all precautions. Everything will work out fine.”

Her period is late, then later. Then it arrives, after all. Then, a few days after that, the mailman comes and more outfits arrive: edible panties, a studded bra, this S-and-M combo with a zippered gimp mask even Maxine couldn’t tolerate during the act. Another outfit had these elastic straps that I could use to pull her toward me, creating a leverage that, whenever utilized, never failed to prompt the dogs to bark.

“My goodness,” I say after rolling off her for the umpteenth time.

“There is no way that didn’t just get the job done.”

Our real estate agent calls the next morning, after Maxine’s gone. I didn’t even know she had my number. “I’m sorry to bother you,” she says, but your wife hasn’t been picking up. “I just want to know if you’re still interested in seeing the house.”

“Which house?” I say.

“The Colonial your wife had been raving about.”

I couldn’t recall. Apparently, she then informs me, Maxine had a showing setup for that weekend. “If you still want to look,” she says, “we’ll have to move the showing up to tomorrow afternoon. After that, New York State will be shutting showings down, and who knows for how long. It’s a great opportunity, really. You could steal this home, if you wanted.”

The cat-bird seat, she says it’s called.

When I finally reach Maxine to relay the information, she surprises me by saying there’s no way she can call out. Things are too crazy at work right now. “And just so you know,” she continues: “I already picked up a shift tomorrow, anyway. And the day after that.”

Apparently, there are sick people on gurneys lining the halls. Dead bodies stockpiled at the morgue. Once she says this, a cacophony of barking coughs start up in the background as if to remind me of everything we’re up against.

But what about our future? I want to say. What about our children, Max-y? But I’d only be repeating her own words back to her, words I’d ignored for too long.

And anyway, she texts me later on, the Colonial needs too much work. From a quick glance at the listing she can tell the hardwood floors need refinishing; the master bathroom, a serious remodel.

But I can do all that, I say.

Can you? she responds.

Maybe we should buy a few acres, I text her. Build our own house. I could oversee everything and make sure it’s exactly how we want. Could we afford that, you think? There appears to be plenty of affordable options: home kits for prefabricated A-frames and barnaminiums. There are even government subsidized low fixed-rate financing and environmental incentives, I say. What about zoning costs and approvals, she responds much later on. Kafkaesque is a word I’ve never heard her use before. The baby, she insists, would be here before we broke ground. The sound of building would prevent the baby from napping.

A whole day has passed and I never left the couch.

Maxine develops a low-grade fever, a cough. “It’s nothing to worry about,” she tells me, despite all the news reports I’ve saw.

When she tests negative for covid, I know I should be relieved. But at this point, it seems like a curse; I’d take any positive result, that long sought after double line.

She starts removing her scrubs and knotting them in a garbage bag like I’ve asked her to. Then I listen as she washes herself raw in the shower. Finally, she collapses in a towel on the futon beside me.

“I’m sorry I took so long. I fell asleep in there,” she tells me. Already, her eyes closing, aimed off toward the sweet oblivion of sleep—when, suddenly, her cellphone vibrates with a notification from her fertility app.

“Dear God, I almost forgot,” she says, eyes still closed, and pulls me toward

her.

“Hurry up. And if I pass out, don’t stop. Put a baby inside me, daddy.”

“How many people have you seen die, Max-y?” I say early the next morning. Maybe I woke her up.

“Hm,” she says, and rolls around in the sheets some.

“Roundabout,” I say.

She shrugs, not seeming certain. Already, her eyes are closing; before her alarm blares, there are a few minutes of sleep left.

“A few dozen maybe?” Her tone is light; maybe she’s dreaming. Not three months ago, she’d been waiting tables while finishing up her nursing degree; now my wife dreams happily within death’s gaping maw.

“A few dozen?” I say. “Are you positive?”

“No, scratch that,” she says, softly. “Double? Triple? More?”

It gets so I can’t pee right—a burning burrows up inside me like a hot wire every time.

That’s not a symptom, is it? I text her.

Of course not lol, she says.

More and more, she returns home from a sixteen-hour shift having to talk me down, to shove more Q-tips she steals from work up my nose and reassure me that, yes, the one line indicates a negative result.

“If you think it’s safer,” she says, “you can start sleeping on the futon. I’ll understand.”

Did I want that? No. “What kind of concubine would I be, Maxine? If you die.”

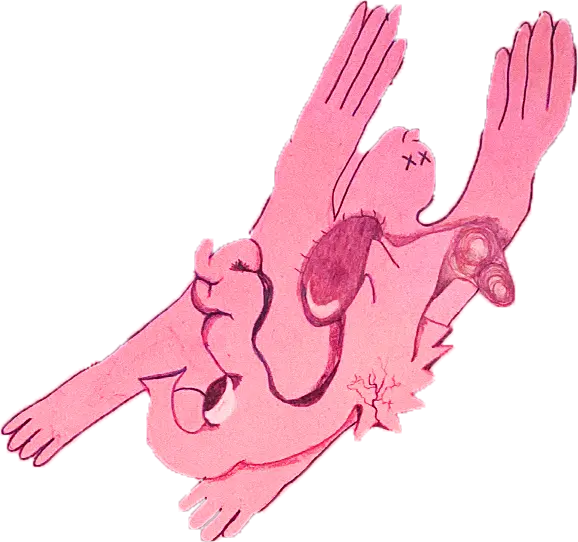

A heroic gesture, I think, until I see the doubting smile she wears. So, to show my dedication to our future, I order another outfit—this time, a leather dog mask, a leather leash, and spiked collar. I figure Maxine will be touched to discover me mashed into an old training crate waiting for her, if a little shocked.

However, upon climbing the stairs to our attic and spotting me, she barely flinches. She takes off her diseased scrubs then whips out of cellphone, taking a photo of me with my leather snout, my lolling pink tongue, my desperate eyes. Then she leaves me there like that while she showers. Me: praying she doesn’t pass out again covered in suds. SEE! I text her, the morning after her period arrives. IT’S PERFECTLY NORMAL!

From the futon, our dogs pressed against me, I spam her with screenshots of the message boards and peer reviewed journals and newspaper articles I find online: Apparently, nature designed our mating for continuous fucking. Since women’s estrus cycles are hidden, their bodies didn’t tip off their more promiscuous male counterparts by squalling like cats or inflaming their asses like baboons. Even dogs. This encourages stronger relationships through fruitless fucking.

Doesn’t that make you feel better? I say. That the difficulty is by design?

Honey, she says, sorry to respond so late. But I keep telling you:

Don’t worry about me. I love you. I’m fine.

Our real estate agent calls to let us know: the moratorium’s been lifted. There’s an open house tomorrow for another farmhouse, out in the onion fields this time.

“Let me talk to my wife,” I say.

But I don’t text or call Maxine after I hangup. Instead, I sit there on the futon, idling stroking the dogs, looking at the listing, taking a digital tour of the house.

With swipes from my thumb, I jump from room to room admiring the open-floor plan, the marble countertops, the window over the sink through which we might watch our future children frolic about the yard.

I look at the back porch and think: Boy, a pair of Adirondack chairs sure would look nice there. Then: This is the one.

But instead of Maxine, I call the real estate agent back to make my offer: ten percent below asking price, as I’ve seen suggested online; a responsible start to the dialogue, I am thinking; only when I do, the real estate agent begins laughing at me. Realty sets in. Highest and best is a term I’m then introduced to.

“Between us,” she says, “the house had already been bid up fifty thousand over asking already.” The jig is up, apparently: All the rich families of New York have decided to flee the city all at once, skyrocketing costs.

Then, there it is: the thin second line. The thinnest of thin; maybe the line actually isn’t there at all. Before leaving for another day of being sprayed with covid, Maxine stands over me in the bed with the test strip pinched between her fingers. She says it’s promising but still inconclusive, that we won’t really know until she takes another one or two.

“I’ll try to take one at work,” she informs me. Then I kiss her goodbye, she goes, and I sit there on the futon watching CNN, stroking the dog, the sun barely risen, watching the death toll ticking higher.

The real estate agent laughs when I call her later that afternoon; I still hadn’t heard anything from Maxine. When I remind her who I am, our price range, the amount of bedrooms we want, she snorts a little; maybe I’ve only misheard her.

“Can you talk into the receiver more clearly,” she says. “You sound muffled.” She wants to know if I have a mask on.

“A mask?” I say, though she isn’t wrong. I do, in fact, have a mask on.

So I unzipper the mouth of the dog mask I’ve taken to wearing around for

swaths of the day. “Better?” I say.

“Yes, better.”

“There’s nothing for us?”

“There is this one house,” she says, laughing now.

“What’s so funny?”

“I could sell anything in this market,” she says, “only not this property. It’s been listed for weeks and I haven’t received a single call. The house is just that disheveled,” she says. “The house is that rank. That diseased. Trust me, you don’t want this.”

“Oh, but I do,” I say.

“I still can’t hear you so well,” she says. “I’m going to hang up now. Call me if you’re ready to get serious.”

Our dog’s old metal training crate presses on my body on all sides. The little squares drag along my flesh, releasing me, bit by bit, as I pull myself from it on hands and knees.

My bones unfurl beneath me for what feels like the first time ever. “Is this better?” I say, my lungs filling with air, animated in a way my dogs aren’t accustomed to, considering the quiet of our days. They cock their head at me with an interest that genuinely worries me.

“Please,” I say. “Just a few more questions: If tested the clapboard on this house: would the paint contain lead? If I tested the crawlspace would the rafters and plywood be speckled with black mold? And what about the drinking water? If I tested the well, would it come back positive for E-coli and lead? Yes? Yes? Are you certain? Are you positive?” I say.

“I’m positive,” she says.

“You are?” I say, but she doesn’t answer.

Harris Lahti is an American writer. His debut novel, Foreclosure Gothic, is available now from Astra House. He is the fiction editor of FENCE.

← back to features