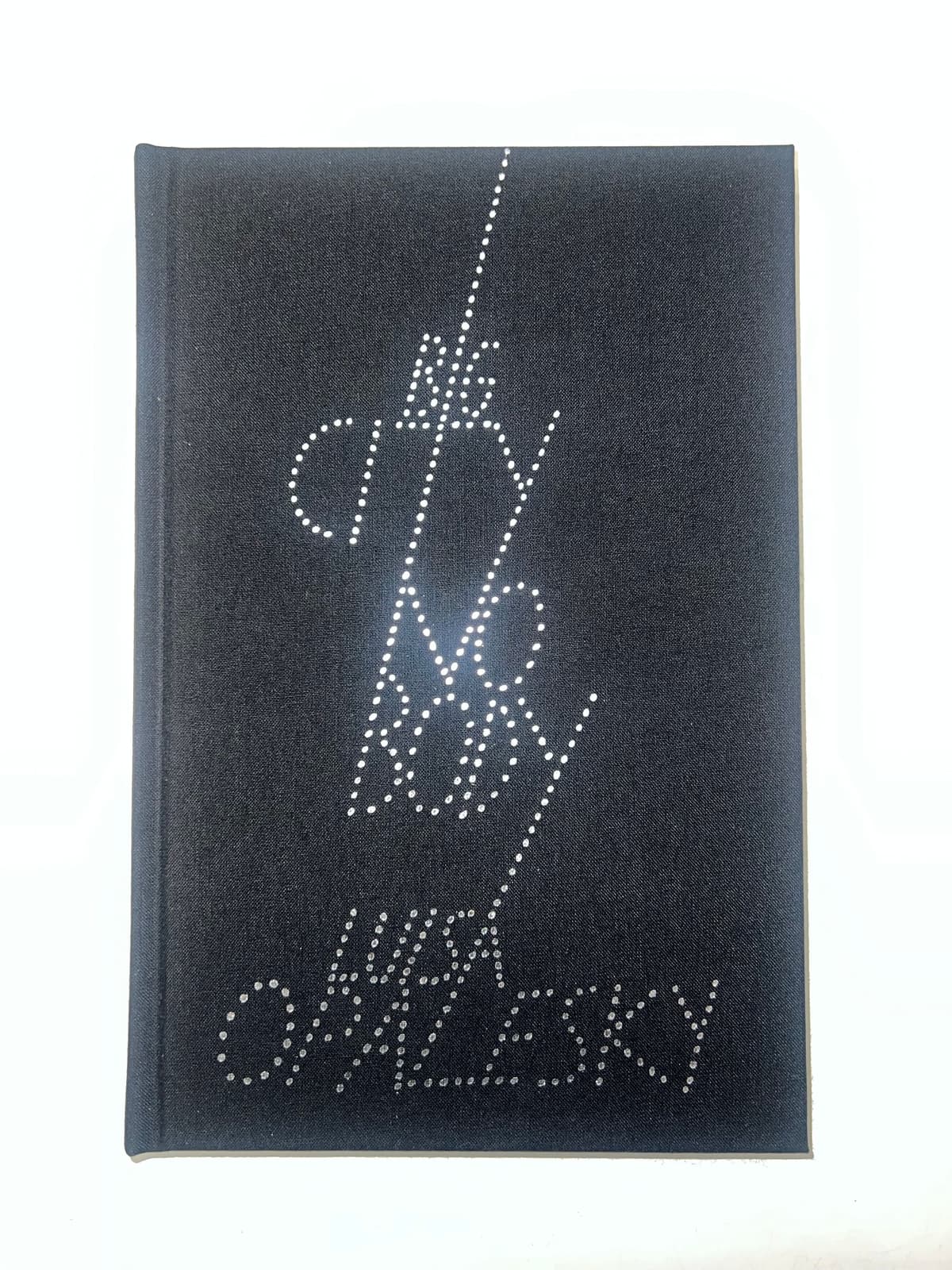

BIG CITY NOBODY

Luisa Opalesky

One of the most beautiful gifts you can give your subjects as a photographer is empowerment.

TESS POLLOK: You’re a New York City-based photographer and you just released the debut collection of your work, Big City Nobody. As of my writing this, it’s sold out on your website, but readers can still buy it at brick-and-mortar locations in Los Angeles like Arcana Books––which has lovely signed editions, by the way–or online at its publisher, Spotz Studios. What inspired you to curate the photos you ultimately chose for the book?

LUISA OPALESKY: I was thinking a lot about the street life of New York, how people don’t have much space to breathe or relax–I always find that place that relaxes me when I see an interesting person on the street or see something unusual happening. I just love the feeling of when someone “strikes my fancy,” you know? Someone who isn’t just a homogenized normie walking down the street. I also find that I’m extremely sensitive and working with a camera is a very centering, meditative process for me. Especially in the context of New York City streets, there’s so much going on, and the camera allows me clarity to capture these moments.

POLLOK: I think the weirdest thing I ever saw on the streets of New York was back when I worked in Midtown. There was this old Eastern European woman selling CDs on the sidewalk and she scalded her feet on something. I’m not sure what, maybe steam coming out of a manhole? I watched her take off her shoes and a man walking down the street helped her pour bottles of water over her burned feet. It was such a surreal thing to watch happening on the street in a major city.

OPALESKY: I love that scene. That perfectly captures what I love so much about street photography–the intimacy. I’m staying in LA right now for the book launch at Arcana and I’ve already seen so much on the street just from walking around town. I’m fascinated by homelessness and unhoused people. I don’t find it fetishistic or offensive to admit that, because I could easily see that happening to anyone. It’s not something that I say with any judgement.

POLLOK: I did want to talk to you about that element of your work. I think homelessness as a topic is something that people tend to slide their eyes away from because it makes them uncomfortable.

OPALESKY: 100%. There’s a photo in the book that stirred up a lot of controversy of an unhoused man with no legs, lying across the sidewalk on his stomach and begging for change. I found him incredibly beautiful. A lot of people told me not to include it in the book, but I felt like I had to because it’s the actual truth of what I’m seeing. Homelessness is a part of the everyday environment of New York City.

POLLOK: I think what’s so crucial about that perspective is that people are uncomfortable with your work around the unhoused population because it implicates them. No one wants to accept that they’re a part of the city and the community that’s doing this to this man. What they really want is to escape their own culpability in his predicament and avoid their feelings of guilt. Instead, you’re making them look directly at it.

OPALESKY: Exactly. They know that they’re a part of it, too, and that they’re not doing anything about it.

POLLOK: Who are your favorite subjects to shoot?

OPALESKY: People who are free-spirited, creative, and open-minded. I like it when my subjects are unafraid about taking risks. That’s important to me, especially because I’ve done a lot of work with celebrities or other people who have these massive PR teams around them and they’re reluctant to take those risks. Photography’s all about capturing the momentum of an exciting moment.

POLLOK: I think risk-taking is a critical skill to maintain as a working artist. It’s something that I see a lot of people losing as they get further along in their career and sink into the monotony of production. I love that feeling; the feeling of cooking pasta al dente and throwing it at the wall, realizing it’s not cooked, and watching it fall. That’s what taking risks feels like to me.

OPALESKY: I think of risk-taking as making an effort to stretch. Stretch your body, stretch yourself. It’s not always easy to wake up in the morning. You have to make an effort.

POLLOK: Do you see people around you, particularly artists, who are afraid to take risks or to make an effort?

OPALESKY: I have a hands-on, learn through doing approach to art. I remember back when I was working for Ryan McGinley I was asked to ride this giant rusty men’s bicycle to a dentists office–that was me biking for the first time in NYC. Chinatown to Midtown on this giant rusty bicycle. I was completely terrified out of my wits, but did it. I really subscribe to a pull yourself up by your bootstraps mentality. You have to accept that if you’re making an effort or taking a risk it’s going to feel uncomfortable.

I just think, in general, that people need to get over themselves. Myself included!

POLLOK: What do you think of therapy?

OPALESKY: Too much thinking about yourself all the time just makes everything worse. That’s why I love this book. It’s like a mirror but I’m not really there. It gets me away from the soul-sucking Instagram bullshit that everyone’s so consumed with and gets me back into real life.

POLLOK: Do you think you’re as free-spirited as your subjects?

OPALESKY: Definitely. I’m not the type of person who’s ever had a five year plan or anything beyond that. People always ask me if I’m going to get married and I tell them the truth, which is that I don’t know. And I don’t care.

POLLOK: One thing I really liked about the book is how it presents the audience with an interesting mix of kinetic and static images. There’s so much movement punctuated by profound stillness–and then back to movement again. I liked moving through that beat by beat.

OPALESKY: Thank you. My editor made a lot of those decisions, but, ultimately, I was happy with them. If it was just me this would have been a 700-page book.

POLLOK: Over what time period were these photos taken?

OPALESKY: They were all shot over a four, five year period beginning with the COVID-19 pandemic. I started shooting a lot more during the pandemic because the city was less crowded and it had less of a nightmare tourist horror element. The people who survived and stuck it out in New York were inspiring to me. I would just be riding my bike every day without anything to do and start taking photographs. It was a crazy feeling, honestly.

POLLOK: I remember that period of the pandemic. It was a lot of things: haunting, inspiring, surreal. I remember walking Wall St. with my friend when it was completely empty in the middle of the day.

OPALESKY: Isn’t it weird to think you’re one of only a few people who’s ever seen something like that?

POLLOK: Yeah, that whole era sometimes feels like a dream. I started this magazine with the first stimulus check I got during the pandemic. I sometimes joke that the experience turned me into a welfare queen, because now I just make art and don’t work very much. I guess I developed a taste for it that never went away.

OPALESKY: I think it’s amazing you were able to escape the 9-to-5.

POLLOK: Me too. It’s something I’m grateful for all the time. My dream for everyone is that they find spiritually fulfilling work.

OPALESKY: I find my work fulfilling in ways I almost can’t describe in words. Typically, I’m wandering the street with three or four cameras on me. I’m not even thinking. It’s all intuitive. I love having more than one camera, it feels like I have tentacles reaching out of me. I also enjoy experimenting with different film cameras.

I got into photography because my mom was documenting a lot as a kid. It sometimes felt like I was a little performer in her house. It was just her and me most of the time and she would be taking photos of me constantly. I had a rebellious streak, so I used to imagine ripping the camera out of her hands and using it to photograph her. That was my introduction. I’ve always been strongly visually inclined, as a kid I loved Betty Boop and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. I remember being so inspired by their cartoonish visuals.

POLLOK: Do you have a favorite photo in the book?

OPALESKY: Yes. “Three Souls at the Opera.” It’s a black-and-white image taken at the Metropolitan Opera. It’s probably the most abstract one in the whole collection.

POLLOK: Which photographers inspire you?

OPALESKY: So many of them. Helmut Newton, for one, and the combination of Helmut Newton and Weegee. Weegee is so funny because he’s so for the people but at the same time he’s such a little shit. You can never get mad at Weegee because of how sincere he is about his subject matter, but he’s always so sneaky. He’ll get to the crime scene before anyone. He’ll be in the movie theater with the biggest flash. Helmut Newton is more of a fashion perspective on that. He loves powerful women and that’s something I really respect. He loves when Cindy Crawford is coming down the stairs and her muscles are rippling and exposed. I always liked that he rejected the sensibility of the frail, emaciated model. One of the most beautiful gifts you can give to your subjects as a photographer is empowerment and I love the way Helmut Newton empowers his subjects.

POLLOK: Do you have any inspirations outside the world of photography?

OPALESKY: David Lynch! He’s such a huge influence on me because of the care and attention he pays to all the characters in his work. Even very small extras, just people walking by, are so fantastically cast. I love the Woodsmen characters from Twin Peaks season three. Some of the most brilliant casting and costuming I’ve ever seen. He represents everything I love about art: celebrating the downtrodden and the people of the street.

LUISA OPALESKY is a New York City-based photographer. Her debut photography collection, Big City Nobody, is available now from Spotz Studios. Signed editions are available from Arcana Books.

TESS POLLOK is a writer and the editor of Animal Blood.

← back to features