BAPTISM AND MANIA

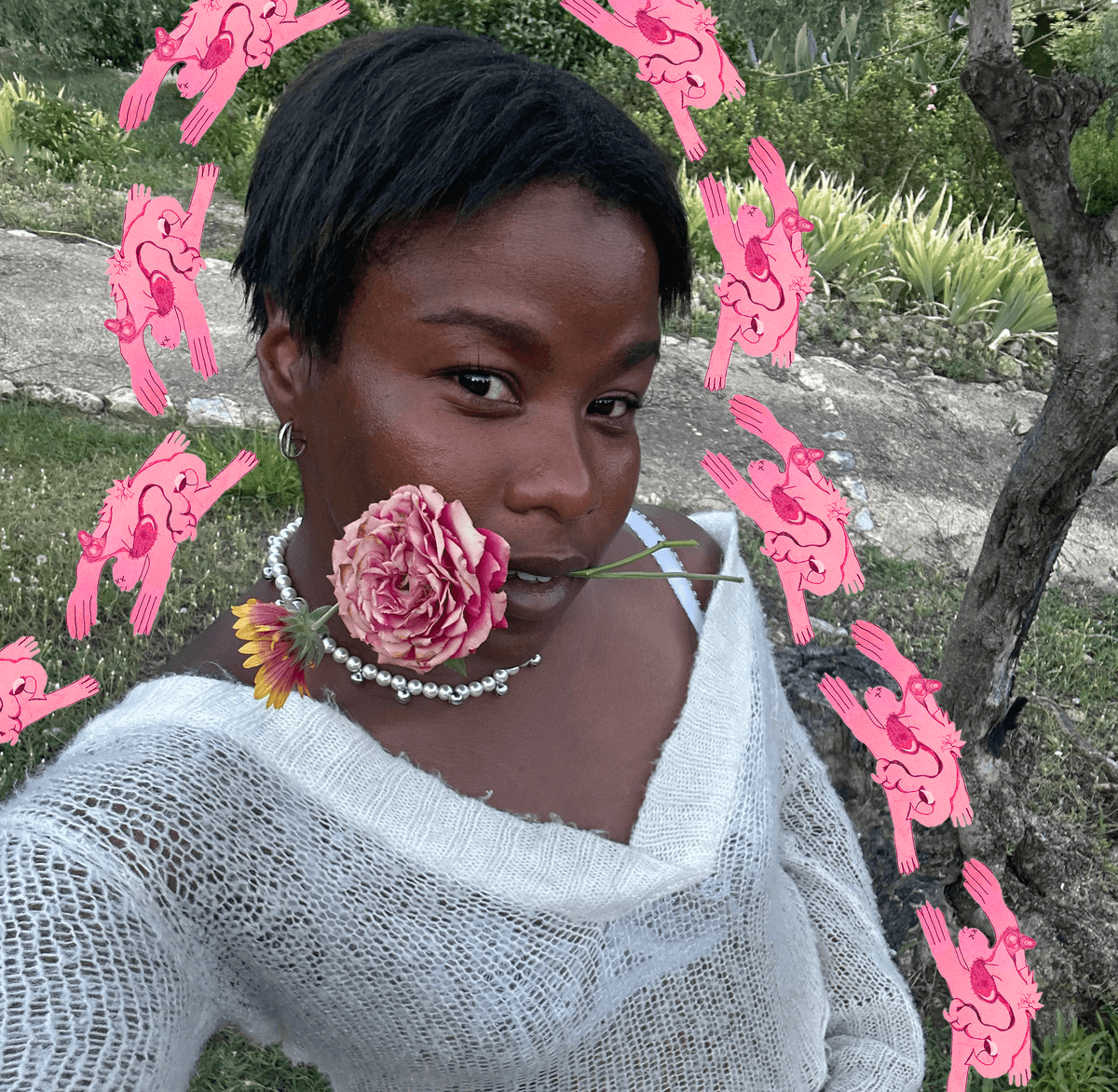

Precious Okoyomon

The human world is not the only world and never has been. This body is not the only body I have. But Did You Die? is a chaotic, confessional snapshot of my 20s…the mania, the prayer, the baptism, the purge.

TESS POLLOK: You’re a visual artist and the author of several chapbooks and books of poetry. I wanted to talk about But Did You Die?, which is your most recent poetry project – it came out from Wonder Press just a few weeks ago. How does the poetry in this book compare to your other works?

PRECIOUS OKOYOMON: It’s a really interesting collection because I can actually use it to chart where I was in my life at the time, so it acts as a snapshot of where I was in my early 20s through to the end of my 20s. It’s all very confessional. The earliest poems in the book are from when I first moved to New York–a really chaotic and transformative time for me. I just wanted to put down what it felt like to have my heart leaking, like, all over the page.

POLLOK: I love that it’s about your 20s because I’m in my 20s–I’m 27 now, which is a rough one. It feels like I’m the gutter. 20 through 26 was great for me. But 27 is pretty disturbing.

OKOYOMON: 27 is so disturbing. I struggled a lot during my 20s–with coming into a selfhood and emotional traumas. But there’s also an abundance of excess that runs throughout the poems. It’s really a journey of discovering who I am and fitting into myself, which is lovely. It’s crazy to look at it all now. I actually read from it a few weeks ago because Theaster Gates hosts this Black artists retreat that I was on, so I read a poem to them that I hadn’t revisited in a long time, “It’s Disassociating Season.” It’s from when I first moved to New York, and I was acting so manic and crazy throughout the entire day, there’s a lot of sex and drugs in that one. It was funny because Theaster was, like, “Damn, I want to hang out with you.” And I was, like, “Don’t. I’m not that fun anymore.” But it was great to write it all down because it felt like this intense confessional purge, which I really needed. It was like a prayer.

POLLOK: I relate so much to the vibe you’re giving off here because I recently got sober and I have the same thoughts all the time. I’m not as crazy or wild as I was in my early 20s. But I did so much disassociating and partying during that era of my life.

OKOYOMON: Exactly. It’s nice to have the feeling that you’re in a different place now, but you can still look back on the past and appreciate it for what it was without needing it to be a part of your present.

POLLOK: That’s how I’m feeling now. I look back on it all now and I think it was all fun. But it’s good that it stopped when it did.

OKOYOMON: That’s why the book is called But Did You Die?. I was trying to capture the chaotic feeling of your early 20s and, like, how urgent and death-imminent everything feels. At the end of the day it’s, like, well, did you die?

POLLOK: You mentioned your journey to finding selfhood. What was that like for you?

Illustration from But Did You Die?

OKOYOMON: I’m constantly reforming my language and discovering new languages when it comes to my selfhood. That’s what poetry is, really. It’s how to make new languages and communicate in new forms. It’s been so interesting to me as someone who is also a visual artist to see how that instinct transmutes in my visual work, like, a lot of what I make as an artist starts out as these poems. I like looking at poems as the seeds of my work and seeing how they grow, evolve, and mature into something new over time. I think But Did You Die? documents my journey towards a new language, which is an eternal process for me. Have you ever read Heidegger’s On the Way to Language?

POLLOK: No, but I’m familiar.

OKOYOMON: That’s a book I care about a lot. It’s about thinking about a practice and forming something–and you may not see an end point for what the practice is, but it’s about cultivating ritual around achieving a practice. For me, this book was that ritual. I wrote every day no matter what. I didn’t know that that was going to be how I found my language, but it was. The book is a portal into form and it gave me space outside of myself where I could be free with rules of my own. A lot of these poems are hectic because they come from a time in my life when I had just moved to a new place and there was constant movement in my life. So, literally, a lot of them started just as notes in my Notes app on my iPhone. I didn’t have a job and I would walk around the city for hours just writing things down in my phone. Eventually those things became poems.

My writing style has changed a lot since then. Maybe because I’m in a more grounded place in my life. But for me, a lot of my writing happens with movement. The way I write now is that usually when I’m traveling, I like to keep a blog every day, and I keep up with journaling. Those things evolve into their own forms. But Did You Die? is in constant motion. This endless tracking of prayers and purge and the chaos that flows out of that. So it’s its own strange ritual. When the language wasn’t enough for me just written down, the phrases evolved into poems. And some of those poems have evolved even beyond that, because a lot of my visual works have titles that are derived from the poems.

POLLOK: I like that poetry is the genesis point for your artistic practice.

OKOYOMON: I tell everyone that poetry is the beginning of my practice and always will be. Even before I conceive of a show, it starts with a poem. A lot of the shows I’ve put on over the past few years were inspired by poems in this book. I think a lot about trying to draw people into the memory archive of poetry and using language as a sort of pollination, taking you back to a place that you can’t even access anymore. How do you say a memory? How do you materialize it inside of the world in a way where it can pollinate the minds of others? Something I’m always thinking about is that things live through me and are within my control–let me explain. A lot of the poems in the book are about my mom or generational trauma, things like that, and it’s nice to have these moments where I realize there’s tons of things flowing through me, that this body I live in is not the only one I have. This body is not the only place I live. Amen to that. But memories are flowing through me constantly, so how do I archive them? And how do I stay present against the onslaught of memory?

POLLOK: Memory is everything. How you carry yourself and your life is reflected in your memories, the quality of your life is contained in how you feel about your memories, narratively speaking. Are there any memories that stick out to you as a highlight of the collection?

OKOYOMON: The whole book feels like one huge memory to me. A lot of the sky songs aren’t memories that I personally hold, but they’re emblematic of this transference–I call it my “feel-knowing”–this deep feel-knowing of love and fragilization I hold. The sky songs were these prayers of channeling and remembering how to hold space for that feeling to come through you. I think that feeling is in everyone and it’s important to remember how to be fragile with yourself and other people, how to witness other people, how to love other people, which is a huge thing for me. That’s at the very core of the book for me. Moments of incarnation of that feeling and ritual, the purge, the baptism.

POLLOK: Oh, that reminds me of a Lorca poem. Do you know the one I’m talking about? “The endless baptism of freshly created things?”

OKOYOMON: Oh my god, no, but that sounds amazing. I love Lorca! I actually got to work with his grandson on a project I did in Madrid, which was so special.

POLLOK: That sounds incredible.

OKOYOMON: His grandson made the music for my piece, “When the Lambs Rise Up Against the Bird of Prey.” I made an animatronic lamb that’s in this end of the world garden–the garden that will survive after whatever becomes of climate change. So it was the lush, sort of apocalyptic garden with a lamb in the middle of it and he made this orchestral piece to accompany the show. The music is based on a piece by Scriabin, a composer that I love, specifically Mysterium, a ten day orchestral piece to end the world.

Illustration from But Did You Die?

POLLOK: What was the emotional texture of your life like when you were writing But Did You Die?

OKOYOMON: Really, really manic. There’s manic peace and manic chaos. I think one of the longest poems in the book is towards the end and it’s about this hurt I was feeling, an intense kind of comedown–you know when you get sort of manic, crash, and then there’s this euphoric sense of realization when you rise up again? It’s about that and falling into the rhythm of being in and out of mania. It’s a book of rebirth in a funny way, because it goes through such extreme highs and extreme lows, which is a lot of what my 20s were like for me. There were a lot of thoughts to decode. It’s all about making ritual from ego death and rebirth, as well as finding people who loved me who I loved. It’s all about the portals I discovered in my 20s, falling into them and realizing they’re just holes and crawling back out again, or vice versa. It’s a lot of falling in and out of what you need to be falling in and out of. The big theme is that love conquers.

POLLOK: I’m glad you brought up the language because I wanted to talk more about that and the way you invoke nature. You flicker back and forth between images of the natural world and your life in New York.

OKOYOMON: I grew up in a deep country suburb of Ohio and I spent a lot of my childhood years sort of just wandering in the woods and doing my own thing. So I feel like my soul is very invested in nature and I’m very attuned to how the natural world is. I’m lucky that I got to grow up from a perspective that the human world is not the only world and never has been. Humans aren’t separate from nature; we’re not, never have been and never will be. That energy recharges me. I could only write what I’ve witnessed and what I’ve witnessed is the world. Nature is a location point for me, it’s what I see and what I understand and how I understand the world around us. I use nature so much in my installations, as well.

POLLOK: You also make reference to holiness and divinity throughout the book. What is your relationship to religion like?

OKOYOMON: Intense. I went to Catholic school for five years. I also grew up going to megachurches my entire life. So, within that context, I had to rediscover my own relationship to God and holy divinity–I had to find space for my queerness, for the love that I was trying to create. I had to make space to be witnessed and for the people I love to be witnessed, which obviously wasn’t a part of the Catholic church when I was growing up. [Laughs] Even when my mom was, like, “Fine, we’ll move to more Episcopalian churches.” So I had to create divinity for myself out of what I personally saw and experienced.

All of the writers that influenced me when I was much younger were Catholic. I really enjoyed a lot of the Christian mystics. The Catholic school I went to wasn’t even a normal Catholic school, it was, like, a traditional Latin Catholic school–which was crazy, picture me wearing a veil at age 16 in suburban Ohio. At the time, I loved Simone Weil and Hildegarde von Bingen. But the mystics were how I discovered my love of poetry. I found there was already this deep well within me for finding sources of abundance. For me, that’s always been in nature. God is constantly around all of us, in the sun, the sky, the earth that regenerates and replenishes itself–that’s what makes it possible for us to live in the world. Everything else is just God’s grace.

Precious Okoyomon is a poet and visual artist. Their latest book of poetry, But Did You Die?, is available now from Wonder Press.

Tess Pollok is a writer and the editor-in-chief of Animal Blood.

← back to features